Rescued from Obscurity:

The Hill 3.4 cc Diesel

by Adrian Duncan

Here we go with an article which I never expected to be in a position to write! We will draw back the hitherto-impenetrable veil which has long concealed the inside story of one of the most elusive and ephemeral model engine marques ever to appear in Britain. We'll be examining the mega-rare Hill 3.4 cc diesel, which made an eye-blink appearance in early 1960 and then disappeared as suddenly as it had appeared before anyone really had a chance to sit up and take notice.

Prior to the appearance of the present article, absolutely nothing of substance had ever been written about the history of the Hill marque. There was of course a very good reason for this, namely, a complete absence of any source material! Indeed, for many years the very existence of the Hill engines was only known to those who were even aware of them through a single advertisement which appeared in the January 1960 issue of Aeromodeller as well as a brief commentary on the Hill 3.4 cc diesel which was published in the same issue of that magazine. If you missed that issue of Aeromodeller, you missed the Hill!

The extreme rarity of surviving examples has actually led many of the relatively small number of people who were even aware of the Hill to assume that the engine never progressed beyond the prototype stage to reach the market. Neither OFW Fisher in his 1977 Collector's Guide to Model Aero Engines, nor Mike Clanford in his 1986 Pictorial A to Z of Vintage and Classic Model Airplane Engines, so much as mentioned the Hill engines, presumably because neither of the authors had access to an actual example to prove their existence.

For many years prior to writing this article, I had personally been aware that at least a few of these engines had somehow reached the aeromodelling community. Many years ago now, a friend of mine actually had a New-in-Box example. Unfortunately, he sold this engine on without first letting me know that he was doing so—this was well prior to the commencement of my latter-day career as a model engine historian! Where is it now? More recently, I was made aware of a second unboxed example in Like New condition which was (and as far as I know still is) owned by the proverbial "friend of a friend". So there were undoubtedly one or two examples floating around.

Further confirmation of this appeared in the form of a short article about the Hill 3.4 cc diesel by John Goodall which appeared in the March 1996 issue of the now-defunct Model Engine World (MEW) magazine. This was based upon John's examination of an as-new boxed example of the engine owned by MEW reader Lou Roberts. However, the text was largely confined to a general description of that specific engine, thus contributing little to the historical record of the Hill marque.

Despite the undoubted existence of the cited examples, the Hill 3.4 cc diesel must surely rank high among the rarest commercial model diesel engines of them all. In a recent on-line discussion thread on rare model diesels in which the Hill came up, one poster characterized the engine as "the Yeti of the British model engine world". Not actually a bad way of putting it—believed to exist, but seldom or never sighted! It was this mega-rarity that gave rise to my long-standing belief that this was one engine about which I'd never be able to write.

It was not until I was able to acquire an actual example of my own thanks to the kind assistance of my good mate Paul Rossiter of Rochester, Kent, England, that I was able to make the first-hand acquaintance of one of these mega-rare engines. Even more fortuitously, I was also put in direct contact with the engine's original owner, Denis Coe of Colchester, Essex, England, who was kind enough to share what he knew about these engines. As things turned out, he knew quite a lot!

The contact with Denis Coe was one of those fortunate occurrences which sustains the faith of the often-frustrated historical researcher by unexpectedly turning the key in the rusty lock of a door leading to a little piece of model engine history which had been assumed to be irrecoverably lost. It's a timely reminder that no story from the past is necessarily lost—it simply takes the right combination of circumstances to allow the facts to be uncovered. Sometimes that requires the injection of a little luck.

It turned out that Denis Coe was far more than just one of the few original owners and users of a Hill model diesel—he was actually a personal friend and flying companion of the two individuals who together created the Hill marque. Better yet, he was more than happy to share his still very clear recollections with me along with a number of "period" images. I'm deeply grateful to Denis for his kindness in this regard. Without his input, none of the following story could have been written, by me or anyone else.

As a result of these circumstances, I've been granted the privilege of being put in a unique position to relate something of a story which I never expected that I or anyone else would be able to tell—the saga of the Hill model engines. Since I am strongly opposed to the "hoarding" of knowledge by so-called "experts", in my book being presented with such an opportunity places me under an obligation to take full advantage of it by sharing the results as widely as possible. That being the case, best get right to it...

Background

The instigators of the Hill model engine venture were two individuals named John K. Hill and Roy Rutter. According to their friend Denis Coe, these gentlemen were partners in a precision engineering business called Rutthill Engineering (no prizes for deducing the origin of the company name!), which had a machine shop on Oxford Road in Clacton-on-Sea, Essex, England. As far as Denis can now recall, Roy Rutter looked after the business and financial end of things, while John Hill was responsible for the engineering side. In keeping with this division of responsibilities (and as implied by its name), the Hill 3.4 cc diesel was primarily designed by John Hill.

Both John Hill and Roy Rutter were members of the Clacton Model Aircraft Club, of which Roy's father was the club Secretary during the period of which we are speaking. Aeromodelling clearly ran in the family! Denis Coe was a fellow club member and regular flying companion of the two partners, thus knowing them very well on a first name basis. Most of their flying back then was done at Jaywick Marshes, on the coast just to the south-west of Clacton-on-Sea (see attached map).

The club members flew a wide variety of model types, including free flight gliders, power duration models, flying scale models and control line models of varying types. Denis recalls that Roy Rutter was strictly a free flight specialist, while both John Hill and Denis flew control line as well as free flight. As time went on, Denis developed a keen interest in control line combat and team racing, becoming a regular competitor in contests which he was able to attend. Denis was also the first of the group to try R/C flying, a branch of the hobby which he still pursues today over 50 years on, some 65 years after building his first model (a glider) at age 13! By contrast, John Hill was not himself a contest modeller, preferring to fly just for the fun of it as well as assisting others who were involved in competition.

Denis has shared an interesting anecdote from this period. Apparently, Roy Rutter had a flyaway with a KeilKraft Slicker when the engine shut-off failed. The club members watched in dismay as it headed out to sea, eventually going out of sight with the engine apparently still running. Scratch one Slicker plus engine, or so they all though—an expensive mishap! However, Roy had taken the wise precaution of affixing a waterproof label to the airframe with his name, phone number and address. Two weeks later, he received a phone call from the skipper of a North Sea trawler which had just returned to port, saying that the model had been retrieved from the North Sea during the trawler's last trip. If Roy cared to come and collect it, he would find it nailed to the mast of the finder's trawler (presumably as a trophy!) at Sheerness in far-off Kent! Thus the tale had a happy if rather improbable ending!

As Denis recalls them today, John Hill and Roy Rutter were a little older than he was. Since Denis is 78 years old as of 2013, this would make him 24 years old in 1959-1960 when the Hill engines made their all-too brief appearance. It thus appears that the two partners were probably in their latter twenties when they launched their short-lived model engine manufacturing venture. Apologies for the poor quality of the attached image of John Hill, but it's the only one that Denis could provide.

Denis tells us that Rutthill Engineering was established some time prior to the advent of the Hill model engines, engaging in a wide range of precision engineering work, presumably under contract to others for the most part. This being the case, it appears that the development of the Hill model engines was undertaken as a labour of love based on the shared interest of the two partners in model aircraft. The decision to enter this field appears to have been taken at some point in 1958.

During the period when the engines were being developed, it's more or less certain that the company maintained its cash flow by continuing with its other business activities—after all, John Hill and Roy Rutter still had to pay the bills! The model engine development venture was doubtless viewed very much as a sideline which was piggy-backed onto the company's mainstream work program as time permitted.

The introduction of a new commercial model engine design presupposes that the promoters had a target market in mind for their new product. The fact that the Hill engines had a displacement of 3.4 cc appears to leave little room for doubt that the primary target markets in this instance were control line combat and stunt. At the time when the Hill engines made their appearance, the rules for the then-popular control line combat class as promulgated by the Society of Model Aeronautical Engineers (SMAE) allowed the use of engines of up to 3.5 cc (0.21 cuin.) displacement. Moreover, diesels in the middle-displacement category were still in fairly widespread use in stunt models during the late 1950's in Britain, especially among the relatively numerous "fly for fun" crowd.

There was no team race category in which an engine of this displacement could be competitive. Moreover, the Hill did not comply with the FAI displacement limit of 2.5 cc for International free flight competition, nor could it compete with the larger engines then much favoured in the Open Power class. Finally, it was significantly larger than would have been considered ideal by the numerous beginners and sport-fliers who were then active in Britain (myself among them). This left control line combat and stunt as the only possible categories in which the Hill engines could realistically hope to compete, at least in un-throttled form.

As of late 1959, the top engine in the combat category was the 2.5 cc Oliver Tiger Mk. III, particularly in its factory-tuned guise. Although giving away a full 1 cc to the class displacement limit, the tuned Oliver's output of around 0.365 BHP @ 18,000 rpm (based upon Peter Chinn's August 1961 test in Model Aircraft) put it comfortably ahead of all of the contemporary commercial British diesels of up to 3.5 cc displacement. Moreover, with a weight of 5.5 ounces (156 gm), it enjoyed a substantial weight advantage over all of the 3.5 cc opposition apart from the less powerful A-M 35 (that's 3.5 cc for our American readers!).

A well-prepared A-M 35 could give the Ollie a good run in a combat context—Gordon Cornell used one to very good effect in the late 1950's, while I myself did well using a modified A-M 35 much later in Vintage diesel combat. However, much of the A-M's effectiveness was due to its unusually light weight of only 4.4 ounces (125 gm) which greatly facilitated the achievement of low wing loadings. Its relatively moderate price of �3 9s 6d (�3.47) was also an attraction for many fliers. The 1959 FROG 349 BB was initially developed primarily for combat applications, but required skilful reworking to match the tuned Ollie for power and was significantly heavier in addition. The 3.5 cc offerings from E.D. and D-C Ltd were never in the running at all, both being of quite unsuitable layout as well as being well down on power compared to the Ollie.

Since the FAI limit for International competition was set at 2.5 cc (0.15 cuin.), much of the development focus of model engine manufacturers was centred upon that displacement category. A competitive 2.5 cc engine enjoyed a far broader potential customer base given the number of classes for which it was eligible. Engines of 2.5 cc displacement or less also possessed considerable attraction for beginners and sport fliers who then as always significantly outnumbered the hard-core competition crowd. However, the downside was that new products in this category faced considerable marketplace competition from both domestic and overseas manufacturers, which did much to offset the positive effects of the larger market.

Even so, it seems a little odd that the partners in the Hill venture chose the displacement that they did for their new model. In all probability they were principally influenced by the fact that they would face far less direct competition in the 3.5 cc category than they would with an offering of 2.5 cc or less, which would have dropped them right in at the deep end in terms of the domestic and international competition which they would have to meet. The downside of course was that the potential customer base was also far smaller. There are always trade-offs involved.

The above factors clearly imply that John Hill's goal in designing the Hill 3.4 cc was to develop an engine for control line combat and stunt that would beat the Oliver opposition while also undercutting it in price terms. The relatively high cost of the Oliver, particularly its �8 15s 0d (�8.75) price tag in tuned form, rendered the latter goal eminently achievable. That said, the specification of the Hill demonstrates that top performance and high quality outranked the lowest possible price as major objectives. A well-built 3.5 cc engine that made best use of its displacement advantage to outperform the Oliver while also undercutting it in price terms would likely stand a fair chance of success in the control line market as it then existed.

The Hill 3.4 cc Diesel Appears

It's evident from the very limited record that the development of the Hill 3.4 cc diesel must have largely taken place during 1959. The goal was most likely to get the engine onto the market in time for Christmas 1959. If this was the objective, it was not met. The first and (as events were to prove) the only advertisement for the Hill engines appeared in the January 1960 issue of Aeromodeller.

This advertisement stated that the engines were made by Rutthill Engineering Co. of 31 Lake Walk, Clacton-on-Sea, Essex. We already noted that the company's machine shop was located on Oxford Road, which is a considerable distance from Lake Walk. However, there's no mystery here—Denis Coe informs us that the Lake Walk address was actually that of Roy Rutter's private residence. It thus appears that the engines were manufactured on Oxford Road and marketed from Roy Rutter's home. John Hill apparently lived at an address on The Street in nearby Little Clacton at the time in question.

The fact that the engines were advertised from Roy Rutter's home address as opposed to the Oxford Road location at which they were actually made supports the notion presented earlier that the model engine venture was seen from the outset as a sideline to the main business activities of Rutthill Engineering. There was a clear intent to keep the model engine marketing very much at arm's length from the company's other activities. The idea was presumably that if the model engine venture fell flat on its face, this would not reflect upon the company's overall business reputation.

The advertisement claimed that the engines were "hand built by precision engineers". The quality of their construction is certainly consistent with this claim. The quoted price was �5 19s 6d (�5.98 in modern money) including Purchase Tax, which undercut the price of the standard Oliver by a modest amount and was considerably less than the price of the tuned Oliver. The engine was said to be available in both disc-valve and reed-valve versions. The disc valve was described as being machined from high-grade Tufnol. Glow-plug models were also offered. Trade inquiries were invited, implying that at this stage the manufacturers had yet to establish any kind of distribution network.

This latter impression is confirmed by the fact that the box labels identified Rutthill Engineering as both the manufacturers and distributors of the engines. Denis Coe believes that all of the engines which did end up in the hands of modellers and the media were supplied directly by Rutthill Engineering from the Lake Walk location—he does not recall them ever having reached any of the local model shops in the Essex area. This is consistent with the fact that I have been unable to find any mention of the Hill 3.4 in any nationally-advertised model shop listings for the period.

That said, the box which was still with Lou Roberts' example at the time of the previously-mentioned 1996 MEW review reportedly displayed a price notation of �5 2s 3d (�5.11), somewhat less than the price quoted in the advertisement. This may simply be the price at which the engines were cleared out by Rutthill Engineering following abandonment of the project, but it is also possible that it could be a model shop price tag. We'll probably never know.

Returning to the announcement of the engine, the Hill 3.4 cc diesel was mentioned in the "Motor Mart" feature of the same January 1960 issue of Aeromodeller. The relevant quote read as follows:

Another new engine is the Hill 3.4 cc diesel which will also appear in glowplug version, and reed instead of rotary disc induction should the purchaser prefer reed advantage of omnidirectional running. On the standard engine, a Tufnol disc is used, the shaft is supported by two Hoffman ball-races, and great attention has been paid to selection of materials. External finish is equal to the highest standards, with a vapour blasted crankcase casting and very highly polished machined surfaces. One striking feature is the early exhaust port opening and depth of these ports. The prototype indicates handsome performance to be expected from production versions.

An illustration of the engine was included with the article along with the caption "The Hill 3.4 cc diesel prototype shows sturdy construction and excellent external finish" Taken together, these two commentaries clearly imply that the engine reviewed by the magazine was characterized by the makers as a pre-production prototype as opposed to a production model. Indeed, it would appear that the initial advertisement and associated article are better seen as advance announcements at the prototype stage than as signalling the actual release of the engine onto the market. That said, the intentions of the manufacturers were clearly serious, as witness the fact that they did get around to making up a number of labelled boxes for the engines.

As far as I can determine, these two references were the engine's sole appearances in the contemporary modelling media. The advertisement claimed that a published test was "forthcoming", but this never materialized. Presumably the engine was withdrawn before Ron Warring of Aeromodeller got around to testing it!

It would appear that the manufacturers proceeded with great caution, first developing their product through the construction of a number of prototypes and then in all probability commencing their promotional campaign by making a small batch of engines with which to test the waters. A few of these engines were seemingly sent to representatives of the modelling media, prompting the previously-mentioned "Motor Mart" article.

This being the case, it's really rather odd that Peter Chinn, the resident model engine guru at the competing Model Aircraft magazine, never appears to have so much as mentioned the Hill engines at any time. It's hard to imagine how this came about...it seems inconceivable that any new manufacturer wishing to draw attention to his product would have omitted sending an example to the most respected model engine commentator of the day.

Other examples from this initial batch were apparently distributed directly to various friends and acquaintances among the active aeromodelling community in order to get a feel for the engine's prospects for competition success through field testing. Denis Coe was one of the manufacturers' acquaintances who took full advantage of this opportunity. He acquired the illustrated example directly from John Hill and promptly installed it in a Razor Blade combat model, then one of the leading designs in common use in Britain. Amazingly enough, Denis still has that model today, in rather tatty condition but nonetheless structurally sound. Those old models were tough—a far cry from today's "disposable model" syndrome! Denis reckons that this one would still fly if it was re-covered!

In Denis's recollection over half-a-century on, his engine proved to be "superb", having a clear performance edge over the predominantly Oliver opposition. Perhaps even more interestingly, Denis also recalls that his engine had the edge on other examples of the Hill 3.4 cc model! Both of these claims clearly merited investigation, as we shall see later.

Denis's recollection that his engine had the legs on the Ollies directly contradicts Lou Roberts' comment to John Goodall that one of his club-mates tried an example of the Hill in a combat model but found it to fall short of the performance delivered by a good Oliver. I wondered initially if Lou could be imperfectly recalling Denis's combat efforts in making this statement. However, Denis tells me that he has never had any contact with Lou Roberts at any time. Lou must therefore have been speaking of a different individual whose experiences were less positive than Denis's.

Despite this dichotomy of recollections, Denis did apparently achieve some success with his Hill-powered Razor Blade. As far as he can recall today, his best showing was at a contest held at Enfield, Middlesex, in which he reached the combat final against the Oliver and Rivers opposition but lost out to the eventual winner. Thankfully, the engine came through the combat wars more or less completely unscathed apart from a few of the usual marks of use, most of which were easily cleaned up. Denis was clearly not a crasher...

Apart from their efforts to make their new design visible to the British aeromodelling community through media promotion as well as direct distribution to friends and acquaintances, it seems that the initial marketing efforts of the two partners included an attempt to generate interest from America, where diesels continued to maintain what amounted to a "cult" following among active modellers. It's an often-overlooked fact that although the relative popularity of diesels was very low in the USA in terms of user percentage among the modelling public, the sheer size of the US market meant that by British standards there was still a worthwhile sales potential there. Most British model diesel manufacturers made efforts to generate some level of American interest in their products, PAW, E.D. and Rivers being notable examples.

Based on his personal interactions with John Hill and Roy Rutter at the time in question, Denis Coe states categorically that to his certain knowledge a number of engines were sent to the USA. It seems likely that these were in fact sent to US wholesalers in an effort to generate quantity orders from them. It would appear from subsequent events that these efforts were unsuccessful. In any case, the partners would doubtless soon have learned what a number of others came to realize the hard way—the potential profits from any sales that were achieved in America were minimal at best since wholesaler discounts in that country were far higher than those in the UK. As a result, the only people who really made money were the wholesalers, since they controlled the majority of the available profit margin.

A further factor affecting the potential profits arising from US sales was the unsavoury but nonetheless well-attested fact that dealing with US wholesalers carried a level of risk to overseas suppliers during the period in question. In the laissez-faire business climate of North America, certain US wholesalers were notorious for intentionally dragging their feet on payment (pleading cash flow difficulties) and then offering a reduced payout to settle the matter to their advantage. It appears that some kind of difficulty of this nature had much to do with the 1963 demise of the highly-respected Rivers model engine range.

Having reviewed the manner in which the Hill 3.4 was promoted at the outset, let's have a look at the product with which the company was attempting to gain a share of the model engine market.

The Hill 3.4 cc Diesel Described

Due to the extreme rarity of surviving examples of the Hill engines, it's impossible to be absolutely definite about the number of variants which were actually made. We previously noted the advertised claim that the engine was available in both disc valve and reed valve variants and that glow-plug models were also on offer. However, the sole model illustrated was the disc valve diesel model with horizontal intake venturi.

Up to the time of writing (2013), I have yet to see any evidence either at first or second hand for the actual existence of either a glow-plug version or a reed valve variant of the Hill 3.4 cc model. It seems likely that such products were planned but never actually produced.

At present we have hard evidence for the existence of only two distinct variants of the engine. One is the model which was illustrated both in the advertisements and in the Aeromodeller article to which reference has already been made as well as being the subject of the March 1996 MEW article. We may as well follow the lead of Aeromodeller by calling that the "standard" version. The other is the ex-Denis Coe downdraft carburettor variant which I was fortunate enough to acquire, as illustrated here.

Although I have had no opportunity to examine examples of both variants simultaneously, it's clear from the available descriptions that the two models differ significantly in design terms. It's thus necessary to describe them separately. Since the "standard" version seems to be the intended main variant, we'll start with that model.

Beginning with a few vital statistics, the engine was significantly oversquare in terms of its internal geometry. Bore and stroke were cited as 0.687" (17.45 mm) and 0.562" (14.27 mm) respectively for a calculated displacement of 3.41 cc (0.208 cuin.) and a bore/stroke ratio of 1.22 to 1. It may not be entirely coincidental that these bore and stroke measurements are identical to those used in both the AMCO 3.5 cc models and the A-M 35. In the context of potential US sales, these figures were problematic since they put the engine just over the AMA Class A displacement limit of 0.199 cuin.

One direct consequence of this internal geometry was the unusually squat and compact physical appearance of the engine. A photograph taken by John Goodall in connection with his March 1996 MEW article shows that Lou Roberts' example of the "standard" Hill was little if any larger than the contemporary E.D. Racer of only 2.5 cc displacement. In the context of the engine's potential use for control line combat, this was a very positive attribute.

However, physical size isn't everything. According to John Goodall's MEW article, the "standard" version owned by Lou Roberts weighed in at a rather hefty 6.98 ounces (198 gm). Right away, we see a significant disadvantage which the Hill would have had to overcome with respect to the Oliver—the latter engine only weighed 5.5 ounces (156 gm). The Hill would thus have needed to outperform the Ollie by a sufficient margin to make up for the fact that it would have an extra 1-1/2 ounces to haul around in a model. In a combat context, that's a lot of excess weight, as competitors were then just beginning to recognize. Even in a stunt context, this amount of excess weight would be noticeable unless it was accompanied by a comparable increase in power output.

The engine was based upon a very cleanly-formed crankcase casting which was attractively finished by vapour blasting. This casting incorporated the main bearing housing with provision for two Hoffmann ball races supporting the crankshaft. The backplate was a separate casting which was attached by four machine screws.

The cylinder arrangements were basically conventional by the standards of the day. Given the fact that beating the Oliver was clearly the name of the game, it's a little odd to have to report that the "standard" Hill featured conventional reverse-flow scavenging using radial porting in the form of horizontal milled slots for both exhaust and transfer ports. By the time of which we are speaking, this style of porting had lost favour in high-performance model engine design due largely to the fact that it did not permit any overlap between the exhaust and transfer ports, thus severely limiting the duration of the transfer cycle.

The actual porting employed consisted of three vertically-wide milled slots which served as the exhaust ports, with three rather narrower transfer slots milled directly below the exhaust openings. The three transfer ports were fed by a bypass passage which was formed in the conventional manner by the annular space between the inner wall of the upper crankcase and the outer wall of the lower cylinder. It bears repeating that this would by no means have been considered a truly "high performance" design approach by the time of which we are speaking.

The one noteworthy feature of the porting was the greater-than-normal height of the exhaust openings. This resulted in relatively early opening of the exhaust ports along with a greater-than-average exhaust port area. It's a bit of a puzzle why the designer didn't bring the lower edge of the exhaust ports up a little and thus allow an earlier opening of the transfer ports to match—there would still have been ample exhaust port area in my view.

The cylinder was retained in the normal way using a turned aluminium alloy cooling jacket which was secured with four screws. For an engine having three sets of ports, the use of four hold-down screws was somewhat unusual, but there it was! A notable feature of the jacket was the use of an extremely thick lower fin which was heavily chamfered on its underside.

The cast iron piston had a very high conical crown, the contra piston being contoured to match. A hollow gudgeon pin was employed along with a turned and milled alloy con-rod. The one-piece steel crankshaft featured a full-disc crankweb which was machined away around the crankpin to create a crescent-shaped counterbalance opposite the crankpin.

Both the examples seen in the January 1960 Aeromodeller features and described in the March 1996 MEW article featured a cast alloy backplate with a horizontal intake and a Tufnol disc to control the induction timing. Somewhat unusually for an engine of this type, the integrally-cast intake venturi was centrally placed at the top of the backplate rather than being located at the "ten-past" position more usual in such designs. The disc valve was driven by an extension of the crankpin in the conventional manner.

A few detail differences between individual examples are apparent from the images to which we have access. For one thing, the engines were seemingly made available with the spraybar holes drilled for either vertical or horizontal orientation of the needle valve. For another, there are clear variations in the configuration of the prop mounting hardware. The example owned by Lou Roberts which was featured in the March 1996 MEW article had a wrap-around prop driver, while all of the other examples of which we have images (including my own example) have bobbin-style drivers. In addition, the shape of the alloy spinner nut varies between long and pointed (as in the Aeromodeller images) and shorter and more rounded as in Lou Roberts' and my own examples. The impression given is that the engines were more or less individually assembled.

The quality of construction of the Hill engines was uniformly very high. This was no start-up effort by a manufacturer who was new to the precision engineering field. The fact that Rutthill Engineering had considerable hands-on experience in other fields prior to launching their model engine manufacturing venture is clearly demonstrated by the quality of workmanship which these engines embody.

A Possible Development Model

The above remarks apply generally to the "standard" version of the Hill 3.4 cc diesel as illustrated in the advertisement and associated summary in Aeromodeller and described in the subsequent article by John Goodall. We next have to consider the somewhat different version formerly owned by Denis Coe and now in my possession.

Beginning as usual with the basics, the measured bore and stroke are unchanged from the "standard" model at 0.687" (17.45 mm) and 0.562" (14.27 mm) respectively for the same calculated displacement of 3.41 cc (0.208 cuin.). The illustrated example with downdraft carburettor weighs 7.16 ounces (203 gm)—fractionally more than its "standard" counterpart. Although heavy by control line combat standards, this is actually a pretty typical figure for a 3.5 cc twin ball-race diesel of its era.

Based upon an initial external examination, the three components which clearly differ between the two models are the cooling jacket, the crankcase casting and the backplate. Beginning with the cooling jacket, this appears to be slightly taller, with thicker fins than the "standard" jacket. This presumably reflects the assembly requirements of the different cylinder used in this model (see below). The compression screw is also different, apparently having a smaller diameter thread (2 BA in the case of the prototype).

Turning now to the crankcase, the ex-Denis Coe engine uses a case on which the rectangular section at the rear of the case for the attachment of the backplate is carried all the way forward above the mounting lugs rather than being confined to the backplate mounting area. The presence of several visible casting flaws confirms that this component was gravity cast (probably by sand-casting), although it was clearly machined and fettled prior to being externally vapour-blasted to a clean and attractive matte finish.

Thirdly, this engine features a completely different backplate assembly having provision for the installation of a separate venturi in a steeply down-draft configuration. While the configuration of the intake is very different from that of the "standard" model, its actual location at the top centre of the backplate remains unchanged.

The notion that this example is a prototype is amply confirmed by the construction of the backplate assembly. It is actually formed from two separate elements—the backplate itself and the carburettor mounting extrusion. The backplate proper was machined from bar stock as opposed to being cast, including the provision of a stub spigot in the intake location. The carburettor mounting extrusion was carved out from the solid. It included both the socket for the intake venturi and a socket for the induction stub on the backplate. The carburettor extrusion was fitted onto the induction stub and very securely epoxied in place. The intake venturi is another separate alloy component which is turned from bar stock and secured by a pair of set screws, one on each side.

It's abundantly clear that this composite backplate was an experimental configuration which was created as a one-off for testing purposes. If the decision had been taken to go into production with this configuration, no doubt a pattern would have been created to allow the component to be produced as a unit by casting.

The Tufnol disc valve reportedly featured in the "standard" model is retained, as is the needle valve. The disc and intake register are noteworthy for the careful work which has been put into streamlining them for improved gas flow. Induction timing is approximately 30 degrees ABDC to 30 degrees ATDC, giving a total induction period of 180 degrees. This is supplemented by a sub-piston induction period of some 40 degrees (20 degrees each side of TDC).

The advantage of the downdraft carburettor arrangement would have been that it significantly reduced the length of the engine immediately behind the mounting lugs, thus facilitating the engine's installation closer to the leading edge in a combat model. It would also have facilitated finger-choking in a typical model installation. Finally, it would have allowed the easy addition of an R/C throttle, which may well have been a motivating factor in the development of this variant.

Internally, we find an equally wide range of differences. Starting with the cylinder, both the transfer and exhaust porting are quite distinct from those used in the "standard" model. The cylinder design in fact appears to mirror that of the AMCO 3.5, with five vertically-narrow milled exhaust slots and five internally-formed bypass flutes. The cylinder is actually very similar to that of the AMCO except for the fact that it lacks the external installation threads which were a feature of the AMCO component with its screw-together assembly.

The timing of the cylinder ports is clearly different from that of the "standard" version of the engine. The previously-noted "Motor Mart" article specifically mentioned the unusually early opening of the exhaust ports. By contrast, the timing of the prototype model with its very different cylinder porting is relatively conservative, the total exhaust period being only 134 degrees of crankshaft rotation (67 degrees each side of bottom dead centre). The exhaust ports themselves appear to be far narrower in a vertical sense, while the upper ends of the transfer openings are set about as close to the lower lip of the exhaust ports as would appear practical. Even so, the measured transfer period of this example is a relatively modest 92 degrees (46 degrees each side of bottom dead centre).

Taken together with the unusually early closure of the induction system, it's absolutely clear that the designer's goal was to produce an engine that would perform very strongly at low and mid-range speeds, presumably accepting some sacrifice of top end performance. You can't have it all. We shall have a later opportunity to evaluate the designer's success in meeting this objective.

The crankweb design is also different. The crescent-shaped counterbalance weight which was reportedly a feature of the "standard" model is absent. Counterbalance is achieved solely by milling away segments of the crankdisc perimeter towards the crankpin side. A minor point is the fact that the ball races which support the shaft are Ransome & Marles items rather than the Hoffmann units reportedly used in the "standard" model.

So what are we looking at here? This engine is unquestionably a Hill product, since it was acquired directly from the designer, who was well known to its original owner. Even if this were not so, there are enough design consistencies to make the relationship obvious.

It seems equally clear that this is a prototype model rather than an example of a "production" unit (if that term can be applied to any of the Hill engines). Although all the installation threads in the crankcase remain sound, there's enough thread wear to confirm that the case has definitely been subject to repeated dismantling and re-assembly of its components. It thus seems likely that this was one of John Hill's development crankcases which he used to test various design concepts. It probably saw service in a number of different configurations prior to winding up in the form in which Denis Coe received it. I suspect that the crankshaft too was a development component which had been with this crankcase from the outset.

Prototype it may have been, but this did not stop the manufacturers from lavishing as much care upon its construction as they appear to have done for the "standard" model which was actively promoted. The quality of the engine's construction is well above average—despite the active service which it has seen, all fits and finishes remain outstanding. The fact that the manufacturers went to the extra trouble of vapour-blasting the crankcase despite this engine's prototype status is indicative of a high level of pride in the presentation of their work.

At first glance, we might suppose that this engine preceded the development of the "standard" version of the Hill 3.4 cc diesel. This however is at odds with Denis Coe's recollection that he acquired the engine from John Hill in 1960 after the introduction (and speedy withdrawal) of the "standard" model. He also recalls that the engine was unboxed when he acquired it. These facts require some reconciliation.

In my view, it seems most probable that after the project was abandoned, John Hill simply disposed of his remaining examples to friends and colleagues, including his development models. However, it would be completely natural for him to retain an interest in seeing how the engine would have stood up if it had been released in quantity. This would explain why Denis Coe, then heavily into control line combat, was supplied after the fact with this prototype example to test in competition. No doubt John Hill followed his efforts with considerable interest!

However, this leads us to the next question—it's clear that this example is a prototype, but a prototype of what?!? Well, it could be a "rejected" precursor of the final "standard" model, but it seems equally possible that it was in fact a prototype of an alternative model which was intended for a broader range of applications than the "standard" variant. The application which comes to mind immediately in this context is R/C flying. The prototype model appears to have been designed with a view towards allowing the easy fitting of an R/C throttle. It also had the advantage of being axially slightly shorter than the other variant, thus easing the challenge of mounting it in a situation where space was tight. It would certainly be easier to mount in a combat model since it could be located closer to the leading edge in a sidewinder mounting configuration. In addition, it would take up less fuselage length in an R/C installation as well as having its carburettor far more accessible for choking and throttle linkage purposes.

The other possibility is that this engine with its revised porting and seemingly very different timing represented the next stage in the engine's development in performance terms. This is consistent with Denis's apparently-clear recollection that this engine out-performed an Oliver in a combat model, also outperforming other examples of the Hill itself. It was evidently one of John Hill's "best" examples, hence his willingness to facilitate its use by the competition-minded Denis. We noted that Denis's recollection is in direct conflict with the impressions reported to John Goodall by Lou Roberts. However, the fact that this prototype engine is a completely different design from the standard model makes it entirely logical to expect that there would be a difference in performance.

In the end, the key to understanding all of this lies in the relative performances of the "standard" model and the prototype. We are fortunate in having a yardstick against which to judge this factor—the Mk. III Oliver Tiger. We are told that the "standard" model of the Hill under-performed by comparison with the Ollie. If the prototype variant proved to have an equal or higher performance when compared with the Ollie (as recalled by Denis Coe), the logical presumption would be that it must have a higher performance than the "standard" model (again consistent with Denis's recollections). In such a case, it would seem highly illogical for the manufacturers to have abandoned it in favour of the less powerful "standard" configuration. This would in turn imply that the prototype was indeed a further development of the "standard" model.

Which brings us at last face to face with the obvious question which our readers are all probably now asking with growing impatience—how does this particular engine perform? A fair question—let's find out...

The Hill 3.4 cc Prototype on Test

It will have become apparent from the foregoing discussion that the example of the Hill 3.4 cc diesel now in my possession is not typical of the design as it was publicly promoted. Nevertheless, it is the sole example which we have available for testing. It might be argued that a test of what is undoubtedly a development prototype would not be productive since it would not necessarily be representative of the type. True enough, but the alternative is to do nothing, which will in turn yield absolutely nothing and hence seems to me to represent a complete waste of a great opportunity. At the very least, a test will provide us with some indication of the prototype design's potential.

In any case, that sole advertisement of January 1960 promised that a test of the Hill 3.4 cc diesel would be "forthcoming"! I'd hate to have to bear the sole responsibility for making liars out of John Hill and Roy Rutter! Better late than never—one Hill 3.4 cc diesel test coming right up!

I decided to test this example of the Hill 3.4 cc diesel against the engine which it was undoubtedly designed to beat, the Oliver Tiger Mk. III. I do not own a factory-tuned version of the Mk. III Ollie, but I do have a nice example of the standard engine in the form of engine number T31450. This unit has received a moderate amount of use in free flight service, but remains in first-class original condition throughout. I would objectively say that it should be operating at or near its peak, thus representing a legitimate basis for a direct comparison.

No sooner decided than acted upon! I began by giving the Hill a few shake-down runs at home to settle it down following its dismantling and re-assembly in my hands, using a 10x6 Taipan prop for this purpose. On a spot check following some slightly rich and under-compressed running, the Hill turned this prop at 9,600 rpm—about the same as a Rivers Silver Arrow. This looked promising...

Greatly emboldened, I headed out to the test location armed with both engines plus a range of airscrews which I felt should give both motors a fair chance to demonstrate their respective qualities. The fuel used was my standard diesel combat mix with a good proportion of ignition improver.

I was quite keen to obtain enough data to develop a meaningful power curve for the Hill. Accordingly, I elected to include a far wider range of props than usual in my testing. The Hill seemed sufficiently sturdy to take plenty of hard work, so I wasn't worried about causing any damage. I did however plan to monitor the results and refrain from pushing the engine too far past its peak, wherever that might prove to lie.

First up was the Oliver, which I had previously run on a number of occasions. I just wish that all model engines were as user-friendly as the Ferndown Fliers! Once again, I was reminded of the all-round excellence of the Oliver products—the engine was an undiluted pleasure to test, exhibiting no vices of any kind and running superbly. No prime was required at any time, with first-flick starts being the order of the day throughout.

The results were pretty much in line with those to be expected from a well freed-up example of the Oliver Tiger Mk. III which has been carefully run in and then given some respectful use. The figures implied a peak output of around 0.35 BHP at just over 15,000 rpm. The Hill would clearly have to work hard to beat this one!

Then it was the turn of the Hill, which I had already found to be very straightforward to start as long as a small prime was administered as a preliminary. On this basis, I'd have to rate it as a less easy starter than the Ollie, although that could be said of most diesels! The Hill could not fairly be classified as difficult—it just needed the right approach. If the correct priming routine was followed, a few flicks were all that the engine ever required. It's just that the Hill isn't quite the dependable one-flick prime-less starter that the Ollie is!

Once running, response to the controls was outstanding, making the establishment of settings quite straightforward. Although there were well-defined optimum settings for both compression and needle, neither control was unduly sensitive, making the establishment of settings quite straightforward. Running qualities were beyond reproach—the engine ran completely smoothly and mis-free at all speeds tested.

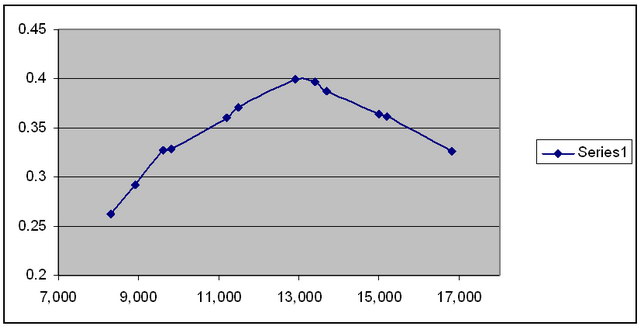

Finally, we get to the question which has been on all our readers' minds—how does the Hill stack up performance-wise? In a word—brilliantly! The results completely confirmed Denis Coe's recollection that this engine had the legs on an Oliver Tiger. In fact, in terms of its peak output it was well ahead of even the works-tuned version of the Ollie if we can take Peter Chinn's previously-noted figures to be representative. The Hill had a clear edge on the standard Ollie on all props tested until speeds were pushed up towards the 17,000 rpm range. By that time, both engines were past their respective peaks in any case. The attached table shows the actual figures achieved on the day, using the same props and fuel on both engines.

| Prop | Oliver Tiger Mk. III | BHP | Hill 3.4 cc diesel | BHP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APC 10-1/2x6 | 7,600 | 0.201 | 8,300 | 0.262 |

| APC 10x7 | 8,000 | 0.212 | 8,900 | 0.292 |

| APC 10x6 | 8,400 | 0.219 | 9,500 | 0.327 |

| Taipan 10x6 | 8,700 | 0.230 | 9,800 | 0.329 |

| Taipan 10x4 | 10,200 | 0.272 | 11,000 | 0.360 |

| APC 9x6 | 10,400 | 0.275 | 11,100 | 0.371 |

| APC 9x4 | 11,700 | 0.298 | 12,900 | 0.399 |

| APC 8x6 | 12,400 | 0.314 | 13,400 | 0.397 |

| APC 8-1/2x4 | 12,600 | 0.324 | 13,700 | 0.388 |

| APC 8x4 | 14,600 | 0.343 | 15,000 | 0.364 |

| Taipan 8x4 | 14,900 | 0.347 | 15,200 | 0.362 |

| APC 7x4 | 16,900 | 0.332 | 16,800 | 0.326 |

The figures for the Hill resolve themselves into a very consistent power curve, allowing for a few missed settings here and there. A few observations may be made on the basis of this curve. First, the Hill is clearly all about torque at the lower and mid-range speeds—a very positive characteristic for both stunt and combat use. Second, peak power is achieved at the relatively moderate speed of around 13,200 rpm, at which speed the output is right around 0.402 BHP. The implied specific output of 117 BHP per litre is well in line with the best standards achieved for production diesels of over 2.5 cc as of 1960.

Hill 3.4cc Power Curve

I suspect that the engine's outstanding mid-range performance is largely down to a combination of a very small crankcase volume for an engine of this displacement combined with the relatively early closure of the induction system, lengthy power stroke (113 degrees) and late opening of the transfer ports. Crankcase pressure at the point of transfer opening will be unusually high because of these factors, resulting in high transfer gas velocities. However, the early induction closure and restricted transfer period will obviously affect performance at the top end, even allowing for the sub-piston induction. Another very instructive example of the trade-offs involved in model engine design—the designer in this case was prepared to sacrifice a high peaking speed for higher mid-range torque.

Whatever the reason, the defining characteristic of this engine is an exceptionally high Brake Mean Effective Pressure (BMEP) at the lower speeds. For those not familiar with this term, it is a theoretical approximation of the average pressure generated in the cylinder over a working cycle. The simplified working formula for our purposes is:

| BMEP (psi) | = | BHP x 6487488 |

| RPM x Disp (cc) |

Since the displacement is factored into this formula, BMEP is a very useful criterion by which to compare engines of different displacements in terms of their operating efficiency—clearly, an engine which develops a higher BMEP at a given speed is working more efficiently than one which does not achieve similar figures at the same speed, regardless of the relative displacements involved. It will also be clear from this formula that the development of high power at lower revs requires the generation of higher cylinder pressures, just as we would intuitively expect.

On the basis of this criterion, the Hill scores extremely high marks. Peak BMEP is reached at around 9,500 rpm, at which speed the figure is around 65.5 psi. This is an exceptionally high figure for a model diesel of 1960 vintage, showing that the engine is working extremely efficiently at these moderate speeds. The prop-rpm figures reported earlier certainly reflect this.

To put the Hill's performance in perspective, as of early 1960 the performance standard for the 3.5 cc diesel category was the 3.49 cc Rivers Silver Arrow, then in its Mk. I configuration. Peter Chinn's measured performance figures for that design (Model Aircraft, February 1960) yielded a peak output of 0.395 BHP @ 15,700 rpm. This translates into a specific output of 114 BHP/litre, less than the comparable figure of 117 BHP/litre for the slightly lower-displacement Hill. Peak BMEP measured by Chinn for the Rivers was around 55 psi at 10,000 rpm, substantially less than the Hill's peak figure of 65.5 psi at 9,500 rpm noted earlier. The fact that the Rivers more or less equalled the output of the Hill, albeit at significantly higher rpm, was entirely due to the fact that its BMEP curve fell off more gradually above the peak.

We thus see that the Hill equalled the Rivers for peak output, and moreover did so at considerably lower speeds on the basis of its significantly higher BMEP at those speeds. The practical implications of this are that the Hill would swing a more substantial and hence more efficient prop than the Rivers without giving away anything in terms of peak output.

Another extremely positive attribute of the Hill's measured performance is the flatness of the power curve. It's very impressive to note that the engine is producing in excess of 0.35 BHP (the measured peak output of the Oliver) at all speeds between 10,500 and 15,800 rpm. Such a wide spread of available power would render the engine far less prop-sensitive than many of its competitors.

In this respect, the Hill once again beats the Rivers (based on Peter Chinn's findings). The Rivers did not reach 0.35 BHP until around 12,300 rpm, after which it maintained a higher output than this all the way up to around 18,000 rpm. It only "caught up" with the Hill at around 14,000 rpm, but the sole reason for this was that the Hill was already past its peak and was on the way back down. Even then, the Rivers was approaching its own peak output, never exceeding the output of the Hill at any subsequent point on its power curve.

So what does all of this mean in practical terms? Well, it means that here we have an engine which is a monster torque producer, delivering real power (by contemporary 3.5 cc diesel standards) at moderate rpm. This in turn would have allowed the use of very substantial props which would do a highly efficient job of moving air. The Hill could handle a larger and hence more efficient prop than ether the Oliver or Rivers opposition while producing more power than either of them in doing so. This would translate directly into a marked difference in model performance, exactly as recalled by this engine's former owner Denis Coe.

On the basis of this showing, a 9x6 airscrew would appear to be a good match for the engine's characteristics in a control line application, while a 9x4 would appear ideal for free flight. For greater airspeed in a control line combat context, I'd probably be tempted to try something like an 8x7 or perhaps even an 8x8. Based on available power absorption coefficients, the engine would likely turn an APC 8x7 at somewhere in the region of 12,400 rpm, speeding up in the air to right around the peak or perhaps a little over.

In summary, this prototype version of the Hill 3.4 cc diesel appears on this showing to have been right up there with the most powerful 3.5 cc diesels of its day. Not only that, but the quality of its construction was equal to that of the best of them. This example came through a long and quite strenuous test with no problems at all, seemingly remaining willing and able to keep on running as long as desired.

What was that word that Denis Coe used—"superb"?!? Seems entirely appropriate to me! Full marks to John Hill and Roy Rutter for a truly remarkable product!

Historical Implications

We noted earlier that the results of a test on the prototype version of the Hill 3.4 cc diesel could have a considerable effect upon our view of its significance. We have the evidence of Lou Roberts to the effect that the "standard" version of the engine failed to match the Oliver Tiger Mk. III in performance terms. By contrast, we've just seen that the prototype variant would have shown a clean pair of heels to both the standard and tuned versions of the Oliver. In fact, it would have given the highly-touted Rivers Silver Arrow a sturdy tussle.

To me, it seems inconceivable that John Hill would have retreated from the level of performance exhibited by this prototype in favour of a model which under-performed by comparison. This strongly supports the notion floated earlier that this was likely a further development of the "standard" model, most likely re-using one of the earlier development crankcases in order to minimize the effort involved. The clear implication is that John Hill had quickly become aware of the general impression that the "standard" model did not come up to the required level of performance, leading him to explore the possibility of getting more out of the layout.

It seems that John was looking for both improved performance and a more convenient and flexible structural configuration. The downdraft carburettor with removable venturi provides evidence of the latter point. However, for reasons at which we can only guess, the decision was taken to terminate the model engine project and return to more general contract precision engineering before this variant could be produced in any quantity.

That said, there can be little doubt that John Hill was extremely confident of this variant's ability to show well in competition. It's impossible to believe that he would have made this seemingly one-off prototype available to the competition-minded Denis Coe unless he was very sure that it would carry his name successfully into the competition arena. In Denis's recollection it did just that, a memory which is completely consistent with the results of the test just reported.

The Marketing Challenge

We've noted that the target market for the Hill 3.4 cc diesel appears to have been the control line combat and stunt crowd, with the R/C market perhaps becoming a secondary objective as time went by. Here we have to return our primary focus to the "standard" version of the engine, since that's the model which was actively promoted by the manufacturers.

Looking first at the engine's potential application for control line combat, we have the anecdotal evidence of Lou Roberts to the effect that it was seemingly unable to match the Mk. III Oliver in performance terms. Moreover, the engine's weight undoubtedly represented a major sales impediment given the fact that combat fliers were just beginning to fully appreciate the critical importance of keeping wing loadings under control.

There was also the fact that the rear induction system employed greatly complicated the mounting of the engine in a typical combat model since it forced the powerplant to be located considerably further forward of the leading edge than normally desirable, at least in a sidewinder configuration. Combined with the engine's higher-than-average weight in a combat context, this had the potential to make the achievement of the ideal balance point somewhat problematic. The revised downdraft variant would have been better in this regard, but it never passed beyond the prototype stage.

Finally, modellers were also just beginning to understand the adverse effect upon manoeuvrability of the gyroscopic effects arising from the heavier airscrews typically used with 3.5 cc engines as opposed to their 2.5 cc competition. This would be another factor which would lead me to try an 8x7 or 8x8 prop rather than a 9x6.

As if this wasn't enough, the announcement of the Hill 3.4 cc diesel more or less exactly coincided with the appearance on the market of a truly formidable and well-publicized adversary in the shape of the previously-mentioned Rivers Silver Arrow 3.5 cc model. This engine was aimed squarely at the same market apparently being targeted by the Hill. We've already seen that it proved to have an outstanding performance, developing close to 0.4 BHP at almost 16,000 rpm, thus evidently seeing off the "standard" Hill in no uncertain terms as well as having a clear edge on even the tuned Oliver. To make matters worse, at a price of �6 5s 8d (�6.28) it was very little more expensive than the Hill. Although at 7.1 ounces (202 gm) it was even heavier than the "standard" Hill, its front rotary valve induction allowed it to be far more conveniently mounted in a typical combat model.

It's true that the prototype downdraft Hill was actually a little more compact than the Rivers despite its rear disc valve induction, but this advantage was really insignificant in practical terms, particularly since this version never seems to have progressed beyond the prototype stage. For the same reason, the fact that it marginally outperformed the Rivers was of course never made public, apart perhaps from a few of those who saw it in action in the hands of Denis Coe.

Right from the start, the new Rivers acquired a reputation as "the" engine to beat in SMAE combat under the rules then prevailing. In the face of this situation, the poor old Hill never really stood a chance in that market. Even if it had attempted to stay the course, the mid-1961 arrival of the PAW 19D would have pretty much settled the issue.

In a control-line stunt context, the weight and configuration of the engine would have represented far lesser objections to its use. However, the appearance of the engine more or less coincided with the general adoption of larger-displacement glow-plug motors for this application, along with a steady increase in typical model size. The Hill thus appeared right at the tail end of the widespread use of diesels in control line stunt, at least until the much later advent of the big-bore PAW diesels.

The "standard" version was not configured to allow the convenient fitting of an R/C throttle, implying that the R/C market was not a primary concern in connection with that variant. If the existence of the downdraft intake prototype can be taken as representing thoughts of a possible entry into the R/C market, it has to be said that in this area too the Hill missed the boat. By 1960 the era of the large purpose-built R/C glow-plug motor had well and truly arrived. Although several diesel manufacturers (including Oliver, IMA (FROG), Rivers and Webra) attempted to crack the R/C market with middle-displacement throttled diesels, none of them achieved much success in the face of the glow-plug's inexorable march towards near-total dominance of that market. An R/C version of the Hill would have fared no better than the others.

It was likely the recognition and no doubt reluctant acceptance of this situation that led John Hill and Roy Rutter to decide right away not to throw good money after bad and abandon the project before it had fairly got started and their financial exposure became problematic. The initial batch of engines which had been manufactured as prototypes and promotional pieces was almost certainly the only batch produced. The extreme present-day rarity of the engine, amounting to near-invisibility, seems to constitute persuasive evidence in support of this view.

The abandonment of the Hill model engine venture by no means spelled the end for Rutthill Engineering, who had prudently kept their powder dry throughout the development and promotion stages of the project. As far as Denis Coe can recall today, the company simply continued their involvement with general precision engineering which had begun before the Hill engines were ever thought of. Denis has no knowledge regarding how long the company remained in business thereafter. All that is certain is that it is long gone today.

It's impossible at this point in time to form any kind of realistic estimate of the number of examples of the Hill 3.4 cc diesel that were in fact produced. In decades of looking, I have only ever seen hard evidence for the existence of three unquestionably distinct examples of the "standard" model, while the prototype downdraft model now in my possession is the sole example of that type which has ever come to my attention. If my earlier deduction is correct that only a single batch was made to test the engine's marketing prospects, then it appears likely that only a few dozen were manufactured in total. There seems to be little question that the number produced came nowhere near reaching triple figures.

Conclusion

In hindsight, it's possible to see that the early retreat of Rutthill Engineering from the ranks of prospective model engine manufacturers was a great pity. The quality of the Hill 3.4 cc diesel shines through in every aspect, while the eye-opening performance of the downdraft prototype is an impressive testament to John Hill's design capabilities. The inescapable conclusion must be that Britain lost a very competent and conscientious manufacturer when the Hill model diesel project was abandoned. If the range had been inaugurated with something a little less specialized and having a broader sales appeal than a high-quality advanced-specification 3.4 cc diesel, we might have seen great things from the Hill/Rutter partnership.

Denis Coe tells me that he lost touch with John Hill and Roy Rutter years ago. When last heard from, Roy was living in Kirby-le-Soken, Essex, a little to the north of Clacton-on-Sea. Seemingly folk from the Essex coast never move very far away, and who can blame them—it's a lovely area, as I know well from extensive first-hand experience.

It's an open question whether or not either or both partners are still with us, since Denis recalls them as being a little older than him, and he was 78 as of 2013. If they are still around, they would undoubtedly be in their early to mid 80's by the time of writing (2013). If any reader has news of either of them, please share it with us, or at least let them know that their long-ago efforts are not forgotten!

Be that as it may, we're fortunate that a few of the excellent engines that they did manage to produce are still with us. We hope that you've enjoyed this look back at one of the more promising examples of the all-too many fine model engines which faded away before their time!