|

|

by Adrian Duncan in collaboration with Jim Woodside

Early Years

Early Years The Genesis of the AMCO Model Engine Range

The Genesis of the AMCO Model Engine Range Ted Martin and the AMCO Years

Ted Martin and the AMCO Years Life After AMCO

Life After AMCO Acknowledgements

AcknowledgementsThis page is a tribute to the late EC "Ted" Martin (1922-2010), the man behind the AMCO model engines that gave so much pleasure to many of us old retreads from the Golden Years of aeromodelling in Britain and elsewhere. Ted passed away on May 22nd, 2010 at the age of 88 years and it's fitting that we should mark his passing with a tribute to the great contribution that he made to the field of model engine design and manufacture.

As we shall see, Ted's activities extended far beyond the model engine field—in fact, when we review his life's work in retrospect, his involvement with model aero engines actually appears as more of an interlude or sideshow than a major focus. A review of his accomplishments reveals a man who was firmly under the spell of mechanical engineering in many different manifestations from model internal combustion engines, through model steam locomotives, to road-going automobiles and high-tech racing cars. Despite this apparent diversification of interest and consequent potential dilution of results, Ted's achievements in all of the fields of engineering to which he turned his hand were impressive, to say the least.

Since this website is all about model internal combustion engines, our primary focus here will be on Ted's involvement with the model aero engine industry. However, it's important that we place those activities in context, and we will accordingly attempt a summary of Ted's overall career in the field of mechanical engineering. We will also present a brief history of the Anchor Motor Co Ltd, the original manufacturers of the AMCO range with which Ted's name will forever be associated among model engine aficionados.

Edward C "Ted" Martin was born in 1922. It has proved difficult to establish many details of his early life, and we'd be grateful to any reader who can shed more light on this period. However, Robin Parker, who was a casual aeromodelling friend of Ted's during his years in Chester, believes on the basis of recollected long-ago conversations with Ted that he was an Oxfordshire lad who came from a fairly comfortable background and was enrolled in a public school, from which he eventually ran away to join the RAF during World War II.

Ted was sent to Canada for pilot training, thus establishing a connection with that country that was to be renewed over a decade later. He became a tow pilot for troop-carrying gliders—a very skilled and exacting task carrying a high level of risk. Ian Russell recalls that Ted was involved in the Arnhem raid, going in with the second wave.The third wave was cut to pieces and the scheduled fourth wave of which Ted was to have been a part was never sent. Ted reckoned that if it had been sent, he would have been extremely lucky to survive.

At the conclusion of the War, Ted found himself at the age of 23 with a passionate interest in engineering and a burning desire to turn this interest into a peace-time vocation. Thanks to the intervention of the war, he had not had the opportunity to acquire any engineering qualifications, so he turned his hand to whatever came up in order to make ends meet. A very successful scheme arose from the fact that hotels in Britain had had six years of deferred maintenance, and Ted got a contract to renew all the lampshades for a major hotel chain. Paper was in short supply, but Ted apparently had little difficulty in arranging for a good supply of excellent heavy duty paper from China for the purpose.

However, there's no doubt at all regarding Ted's interest and innate ability in the engineering field. He was also, in his own words, "modelling mad". Putting these two factors together, it would only take the right opportunity to get Ted fully involved in the model engine manufacturing field which was then very much in an expansionist phase in Britain.

According to John Maddaford, as related to Jim Woodside, Ted's initial foray into the field of model engine design came in 1946 at only 24 years of age, when he designed the Stentor 6 cc petrol engine for Rogers and Geary of Leicester, who had previously made the pre-war Spitfire 2.5 cc petrol engine, as well as the British Wasp and Hornet units. The Stentor appeared in two successive variants and was sold primarily through the Bournemouth Model Shop, where the late Phil Smith achieved so much in terms of model design work under the Veron banner, including the Stentorian design which was created especially for the Stentor engine. The engine was also quite extensively used in model car racing.

John's knowledge of this subject is based on first-hand discussions with Phil Smith. Phil had worked closely with Rogers and Geary on the Stentor project, hence we believe that the information is likely accurate, although we must mention that we have not been able to obtain independant corroberation and since both Ted and Phil both left us just days apart, we can pursue the matter no further.

Having cut his teeth as a model engine designer, Ted was ready for a greater challenge. As events were to prove, such a challenge finally presented itself in 1947 when the Anchor Motor Co Ltd, makers of the AMCO model engine range, decided that they needed the kind of help that Ted could offer.

The Anchor Motor Company Ltd was established in the 1930's in premises which were located on The Newgate, a street in the heart of Chester, Cheshire, England. The company grew into quite a large organization, employing up to 80 staff during its heyday. They were engaged in car sales (Hillman, Humber, Thames and Rootes in later years) as well as operating a major vehicle servicing facility which included both a spray shop and a very extensive machine shop. They were deeply involved in motor engineering, including servicing, rebuilding and re-boring a variety of engines, both automotive and commercial (Perkins diesels, etc). They also made custom vehicles for specialized transportation applications in the agricultural and other fields. The machine shop thus lay at the core of the company's business.

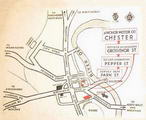

A pre-war Anchor Motor Co. promotional booklet recently discovered by Jim Woodside yielded further details regarding the company�s operations during the 1930�s. As shown on the attached map from the booklet, the company had premises at three different locations. The offices were located on Grosvenor Street, with a small showroom on the ground floor. There was a far larger showroom having space for 50 cars on nearby Pepper Street, while the service department was located round the corner on Park Street (in effect, a continuation of The Newgate opposite). It may appear odd that the address of the company was given as The Newgate, since none of its premises actually appear to have been located on that street! However, The Newgate has long been considered as a location rather than a mere street!

It�s worth noting at this point that the machine shop itself did not share accommodation with the rest of the operation at The Newgate, but was separately located on Victoria Road in the outskirts of Chester to the south-west. It was presumably at that location that the model engines were made.

It�s worth noting at this point that the machine shop itself did not share accommodation with the rest of the operation at The Newgate, but was separately located on Victoria Road in the outskirts of Chester to the south-west. It was presumably at that location that the model engines were made.

During World War II, the company made gun turrets for the Wellington and Lancaster bombers which were the mainstay of RAF's Bomber Command. These aircraft were completed at the nearby Hawarden and Hooton factories where the Airbus is still made today. They also produced tail units and wiring harnesses for the legendary Spitfire fighter. In this way, they made a significant contribution to the war effort.

The Spitfire tail units and wiring harnesses were manufactured at the Pepper Street location in what had been the 50-car showroom. This facility was returned to automotive use after the war, and is still in use today (2011), being occupied by the Habitat Interiors company. It�s interesting that this company still lists its address today as "The Newgate/Pepper Street".

Given the importance of its wartime work, the company had enjoyed a high priority in terms of the allocation of scarce wartime resources and had been able to keep its machine tool inventory well up to spec, replacing worn equipment as necessary. As a result, the company entered the post-war period with a machine tool inventory that was of excellent quality and in fine condition. This was in stark contrast to many of the other firms which were forced to commence their post-war activities with well-used equipment which was, to put it kindly, rather "tired".

The genesis of the AMCO model engine range was related to Jim Woodside by Ted who recalled that Bill Leeman, Managing Director of Anchor Motor, had bought a Swiss Dyno model diesel for his son. Leeman took a good look at this engine and realized that the excellent machine tooling which the company had at its disposal could well be turned to commercial advantage in manufacturing a similar product.

One interesting point that should be made here is the fact that when they entered the model engine business the company consistently used the name "Anchor Motors" on the boxes and instruction leaflets rather than their full name of Anchor Motor Co. This was doubtless done to establish a separate identity for their model engine activities. It�s unclear whether the Anchor Motors entity was every actually registered as a separate company, but it seems unlikely.

Anchor had no design or manufacturing experience of their own with model diesels, which were in any case very much in their evolutionary stage at the time in question. Accordingly, the idea of adopting someone else's design would have had considerable attraction for them.

About this time, a certain Basil Healey of Ilford in Essex was developing his own design for a small model diesel engine called the Midge and manufacturing it in very small numbers in his own home workshop for sale locally. The stereotypical one-man "garden shed" operation, in fact! The Healy engine was made in several displacements from 0.5 cc through 0.99 cc to 1.2 cc. Healy's location is often reported as Rayleigh, Essex, but the late Ron Moulton assured us that Ilford is correct.

Bill Leeman somehow became aware of Basil Healey's design and reached an agreement with him to adopt it with some modifications for his own manufacture. The circumstances whereby this came about are apparently lost in the mists of time—even Ted Martin was unable to clarify this matter. However, the connection most likely came about either as a result of a first or second hand encounter with an example on the flying field or from an article in the model engineering press. It appears that one provision of the agreement was the supply of crankcases to Healy by the Anchor Motor Co, since at least one surviving Healy engine sports what appears to be a standard AMCO .87 case complete with AMCO identification!

In his conversations with Jim Woodside, Ted recalled the Healey design as being far more along the lines of the Mills 1.3 than the subsequent AMCO .87 model. However, the illustrations in Mike Clanford's "A-Z" model engine book reveal a very obvious similarity between the Midge and the AMCO .87. Moreover, the illustrated 0.5 cc replica of the Healy Midge was made by Derek Collin from an actual example of the Healy engine plus some associated drawings, and this fine replica amply confirms the similarity to the AMCO. The Midge had the same mounting hole spacing as the AMCO and as the Ace 0.5 cc for that matter—the three engines were interchangeable in the same model.

The pre-release inventory build-up of the AMCO .87 commenced in around May of 1947. The initial production engines reportedly had only three stiffening webs on the main bearing as opposed to the later four and also had minimal bracing for the engine mounting lugs. Otherwise, they were apparently very similar to the well-known Mk I version of the AMCO .87 with its four main bearing webs and prominent webs on the mounting lugs.

At this point a major problem reared its ugly head—it was quickly found that the engines would not run! A bit of a problem for a new product that was soon to be launched into a very competitive market! The components were apparently manufactured to a given dimensional specification rather than being individually fitted to model diesel standards and as a result, most of the pistons were way too loose.

Clearly the company had to take some drastic action if the engine was to be launched upon the market! They could of course have taken the easy way out and simply thrown in the towel, returning to the other work which still occupied the majority of their resources. Fortunately, however, they chose to deal with the problem rather than run away from it by bringing in outside help to sort out their model engine production problems.

Accordingly, an advertisement was placed in a trade magazine seeking an individual with an engineering background who was knowledgeable about model engines. This advertisement was brought to the attention of 25 year-old Ted Martin who immediately jumped at the chance. A real turning point for all concerned, ourselves included.

Speaking to Jim Woodside many years later, Ted retained a clear recollection of the circumstances surrounding his first meeting with his future employers. He responded to their advertisement and a meeting was arranged at the Regent Palace Hotel in London—a very swanky location indeed. Since neither party knew the other, some form of recognition arrangement was required. It was agreed that Ted would arrive for the meeting carrying a copy of "Aeromodeller" magazine and wearing a tie with a wheel motif—all very Eric Ambler!

The recognition strategy was effective and the meeting took place as arranged. Ted became an employee of the Anchor Motor Co and beyond doubt, his previous model engine design experience with the Stentor helped him to achieve this happy outcome. His new situation naturally required him to relocate to Chester, which he did in mid 1947.

As explained earler, Ted found that upon arrival in Chester, the machine tooling available for the manufacture of the engines was in excellent condition. He also found bins of very well-made components which were unfortunately not matched and didn't fit. The workers were evidently very competent machinists but not surprisingly, had no idea about what constituted the correct fit for a model diesel piston/cylinder set, the fitting technique for model engine pistons, nor of the correct use of the hone and lap to achieve the required fit between two matched components!

So Ted's first task was to train the workforce in the correct fits and finishes for model diesel components plus the appropriate techniques for achieving the desired results. He clearly taught them well, because subsequent AMCO engines were fitted to very high standards. At the same time, he designed the changes to the crankcase casting described earlier to increase the strength of that component.

As a result of Ted's efforts, the company was soon turning out the AMCO .87 to a very acceptable standard and the engine was officially launched upon the marketplace in August of 1947, only a few months later than originally planned. However, this did not immediately translate into the expected sales volumes of the new model. Chester was far removed from the major marketing centre of London, so most sales had to be consummated through the receipt of orders from distant locations. Ted recalled that there was still something of a hangover from the war in terms of consumer expectations—the theory was that if you ordered 50 items, you might get two! Coupled with the engine's relatively high price of 4 guineas (a "guinea" was a quaint way of saying one pound and one shilling; £1/1s/0d), this rather pessimistic consumer viewpoint tended to discourage orders to a significant extent—people preferred to buy what was available locally rather than place orders to remote locations which they believed might not be fulfilled. This of course explains the existence at this time of many low-production engines which were mainly sold locally—the Healy, Foursome, Kalper, MEC, Milford, Clan, and MS (Newcastle) engines come immediately to mind.

As a result of the above factors, the initial market sales projections for the AMCO .87 proved to be somewhat optimistic. Despite this, the company persisted with their efforts and the sales picture improved considerably once the well-known firm, Henry J Nicholls (HJN), of Holloway Roead, London, became the main AMCO distributors and servicing agents. This in turn encouraged further development of the engine. Ted recalled that development was pretty much continuous throughout this period. A Series I Mk II version was released in mid 1948 incorporating a number of quite substantial revisions including a new crankcase. This was further updated in December 1948 by a Series II version of the engine which featured modifications to the transfer arrangements and the working components.

Ted recalled that the goals of these changes were to improve power and simplify the manufacture of the somewhat complex original design. In the latter respect, the changes were successful in that the price of the engine was reduced to �3/12s/6d. Eagle-eyed readers may notice the neat circle of numbers stamped on the head as a guide for compression setting, a Martin Feature later to appear on both of the AMCO 3.5cc models, and the MAN 19 prototype built by Ted himself!

The custom AMCO .87 props which were supplied by the company for use with these engines were made by Gig Eifflaender in Macclesfield. They were initially painted black with yellow tips, but later examples were left in their plain wood finish with an AMCO motif applied with a rubber stamp. The recommended fuel was equal parts of Redex (a well-known British upper cylinder lubricant) and ether—more like a fixed-compression fuel than anything else!

One matter which Ted clarified in his conversations with Jim Woodside was the approach taken to the assembly of the AMCO .87 and the matching of serial numbers on the cases and cylinders. The sequence of operations was as follows:

Ted recalled that this approach allowed for only two re-assemblies before mis-alignment of the induction tube became an issue as the cylinder seat wore down. After this, re-shimming was required. This is why so many AMCO .87's today show the infamous "10 past 12" carburettor alignment! Jim Woodside has personal experience of this—he was involved in the assembly of the Rustler repro AMCO .87's many years later. He recalls the cylinder installation as being the most time-consuming assembly operation of them all. He made a punch and die set to produce the cylinder base shims and then spent an average of some 30 minutes for each engine getting the shimming of the cylinder correct for the desired carburettor alignment. As Ivor F later observed, the only way to make a small fortune from manufacturing model engines is to start with a large one!

By late 1948, with the AMCO .87 well in hand, Ted's thoughts turned to the expansion of the range. By this time he had begun to take an interest in the racing scene which was to dominate his later activities. Robin Parker, who persuaded Ted to modify his Dooling 29 for speed work, recalls that to get to work, Ted used a modified moped to which he had fitted "drop" racing handlebars!

Given his interest in racing, Ted's thoughts naturally turned to the possibility of designing a 10 cc racing engine. When speaking years later with Jim Woodside he recalled being very high on this idea which would have placed AMCO in head-to-head domestic competition with the likes of Nordec, Rowell, and 1066 for a share of a very limited market. It was perhaps fortunate for the company that cooler heads prevailed and the decision was taken to expand the range with a model which stood a far better chance of attracting broader sales interest than a specialized racing unit.

The result of this decision was the May 1949 introduction of one of the all-time classics produced by the early post-war British model engine industry—the AMCO 3.5 Plain Bearing (PB) diesel. The prototypes of this engine were made from the solid without the use of castings—Ted showed Jim a few photos of these prototypes. He confirmed the readily-apparent fact that this design was influenced both by the Arden and Elfin engines, having visited Frank Ellis at Aerol Engineering, makers of the Elfin engines in nearby Liverpool, to discuss the pros and cons of this approach.

Confirmation of some level of ongoing interaction between Ted and Frank Ellis is to be found in the recollections of a friend of Jim Woodside's, who remembers meeting Ted, Frank Ellis and Mike Booth (a talented control-line flyer and one of the first users of the Elfin 1.8) at a control line meeting in Chester at around this time. His main surviving recollection of this encounter was that Ted seemed to him to be rather "posh", which is of course in keeping with Robin Parker's previously-summarized recollection that Ted was blessed with a somewhat privileged early life by comparison with many of his more northerly contemporaries.

By developing a design in the 3.5 cc displacement category, Ted avoided placing the Anchor Motor company in direct competition with the then-popular Elfin engines designed by his mate Frank Ellis, since there was no 3.5 cc Elfin model. This was a good strategy, because the AMCO 3.5 PB had relatively little competition upon its introduction (the ED Mk IV didn't appear until later in the year) and proved to be an instant success despite a few teething troubles caused by a somewhat flimsy shaft in the original versions, plus an inappropriate choice of con-rod material—even Ted was still learning! By this time, the distribution and servicing of the AMCO range had been entrusted to HJN, whose repair shop under the direction of Dennis Allen was kept busy for a while replacing those components on the original AMCO 3.5's. However, Ted learned very quickly, and the design flaws were soon corrected.

Because of its very high power-to-weight ratio, the AMCO 3.5 PB quickly became one of the favoured engines both for control-line stunt and free flight use. It sold very well indeed and it was this engine which really put AMCO into the forefront of the ranks of British model engine manufacturers. A glow-plug conversion kit was quickly developed and a factory-built glow-plug version of the engine appeared in mid 1950, although the engine was never as popular in glow-plug form as it was in the diesel version.

By the end of 1950, with the AMCO 3.5 PB was nicely sorted and selling well, Ted was ready for a new development challenge. The market was still not receptive to the 10 cc racing engine of Ted's dreams, so Ted did the next best thing by developing the famous AMCO 3.5 Ball Bearing (BB) model. This was unveiled in August of 1951. Ted recalled that the rear disc-valve twin ball-race design was strongly influenced by the McCoy and Dooling 10 cc racing engines which were his pride and joy at the time.

By this time Ted's interests were well and truly focused upon the development of high-performance engines. It was clear to him that he would never have the opportunity to do this kind of work while employed by the Anchor Motor Co. However, General Motors (GM) in Canada were planning the development of a new V8 engine and were seeking engineers to help in this effort. In late 1951 Ted accepted a position with that company and ended his association with the AMCO range, leaving them very much on a high note as a result of the success of his ultimate design for them—the AMCO 3.5 BB.

Ted's move was fortuitous as events were to prove, because the involvement of the Anchor Motor Co with model engines was coming to an end in any case. Ted's departure may actually have had something to do with this. Following the outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950, the company had received a major contract from the Ministry of Defence to develop and manufacture a military version of the 500 cc twin-cylinder Triumph motorcycle engine for the purpose of powering field generators, pumps and the like. Once they reached the manufacturing stage of this project, they found themselves with insufficient resources to maintain production of the very popular 3.5 cc engines (PB and BB) at levels which matched demand.

Ted's departure was presumably the final straw, so shortly afterwards, the AMCO name (which by then had considerable brand recognition value), designs, components and dies were offered for sale. They were eventually purchased by a newly-formed London-based company, the Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co of Alperton, Middlesex (near Ealing), who carried the AMCO name on for a few more years. But that's another story, to be related elsewhere.

The Anchor Motor Co remained in business for many years following the end of their involvement with model engines, finally closing their doors in 1983. Today the location at which they produced the AMCO engines has been extensively redeveloped, much of it being absorbed by the Grosvenor Shopping Centre, although The Newgate still exists.

Ted Martin sailed for Canada on January 5th, 1952 (a date noted by Peter Chinn in his April 1952 "Accent on Power" column in Model Aircraft). His major objective in making this move was to join the engine development staff of GM Canada in St Catherines, Ontario, but his interest in models and model engines remained undiminished. Prior to leaving for Canada, he had discussed his plans with his good friend Peter Chinn. Those plans included the establishment of Ted's own model engine company, the initial product of which would be an ultra high-performance twin BB .049 diesel with which to compete in the huge US 1/2-A market. Chinn remembered this matter very well indeed because Martin had apparently invited Chinn to join him in this venture. Perhaps wisely as things turned out, Chinn declined.

The planned .049 diesel project never got off the ground, likely due to funding difficulties. Although he was now involved in full-size engine development, Ted's fascination with model engines continued unabated. In any event, the job with GM didn't pay all that well and an extra source of income would therefore be most welcome. Ted quickly found a remunerative outlet for this ongoing interest by acquiring the position of resident engine tester for Model Airplane News, beginning in December 1952 and going on to produce some 43 test reports for the magazine before stepping aside in June 1958 due to the increasing pressures of other work. Interestingly enough, he was replaced by none other than his old mate Peter Chinn, who had occasionally filled in for him at MAN when Ted was unable to deliver a test report on time due to other commitments.

Ian Russell recalls Ted commenting that the position with MAN actually paid better than his supposedly full-time job with GM Canada! As a result, Ted was soon quite comfortable financially and was able to fund his entry into the world of motor sport which was to dominate much of his later working life, tuning and racing an MG sports car. This got him noticed by MG, resulting in him doing some work for MG on the brakes of their famous 1958 MGA twin-cam design.

Ted also found time somehow to continue his model engine design activities, publishing details of a 3.5 cc twin ball-race barstock engine in Model Airplane News, which bore more than a superficial resemblance to a certain 3.5 BB engine once made by AMCO! The construction article appeared in three parts beginning with the April 1956 issue, with a fourth very well reasoned part dedicated to the black art of running-in appearing in the July issue. This contains the reason it is misleading—to say the least—for anyone to say how long it will take to break-in a home built engine, and how run-out (or not), it may be afterwards!

One consequence of Ted's considerable stature in the North American modelling world through his MAN connection was an arms-length consultancy role with the Herkimer Corporation, manufacturers of the OK engines. This may have come about as a result of Ted's very favourable reviews of several OK products, including their .049 and .075 diesels. The relationship culminated in the offer of a full-time job at Herkimer, which Ted considered very seriously, going so far as to commence the immigration formalities. However, when confronted with the array of questions asked by the US immigration authorities (this was during the McCarthy era), Ted reckoned that many of them were both impertinent and personal in nature (not that he had anything to hide). So he decided that he really couldn't be bothered and stayed in Canada.

During his lengthy period of service to GM Canada, Ted found himself becoming increasingly drawn into the high-tech world of prototype racing cars. While still at GM Canada, he formed his own British-based company (Alexander Engineering) for the purpose of tuning racing car engines, primarily the Ford 109E-based Formula Junior units. He designed a custom single overhead camshaft three valve cylinder head for Ford four cylinder motors and eventually developed the first of a series of full-bore racing engines destined to bear his name. This was a four-cylinder Formula Junior engine which was ultimately developed into a three litre V8 unit intended to compete in Formula One under the new three litre formula which had been announced for the 1966 season.

Ian Russell has some recollection that the driving force behind the original Martin V8 F1 engine came from an Italian company which was planning to enter F1 in a major way (Ian couldn't recall the name). They apparently got as far as building no fewer than thirteen chassis before a major industrial order deflected them from their F1 ambitions and the project died stillborn. Sadly, this was a recurring theme in Ted's F1 career.

Ted's Formula One unit would have competed against the GM-based three litre Repco engine which actually won the World title that year for Jack Brabham. The Martin V8 was extremely light and compact, utilizing two banks of cylinders with single overhead camshafts and the then-innovative toothed rubber belt drive technology for the camshafts. This had been developed in Canada specifically for snowmobile belts, but Ted was among the first to recognize the potential of the technology for use in engine construction. In later years, Ted reckoned that his good mate Keith Duckworth had basically nicked the idea from him for use in the Cosworth racing engines!

In many ways, the Martin V8 was a technically innovative design. However, the racing version developed only some 270 BHP on carburettors, which was obviously not enough to make it competitive even if it had been ready to race against the Repco-Brabham in 1966. For this and other reasons, the original engine apparently never competed in a Formula One championship race although the Canadian Motorsport Hall of Fame had an example on display for some time.

The Martin V8 engine did see some action on the track in 1966 and 1967 when the London-based wheel manufacturer JA Pearce collaborated with Charles Lucas to create a very short series of F1 cars based on a modified Lotus 35 Formula 2 chassis with a Martin V8 engine somehow shoehorned in. Only three of these cars were built. They had a somewhat chequered career. One of them placed third at Mallory Park in the rain on Boxing Day 1966 driven by Roy Pike, and was then entered for the 1967 Race of Champions, to be driven by Piers Courage. It was quite slow in practise and then bent a rocker while the engine was being warmed-up on race morning and consequently non-started. Courage then crashed it while testing at Snetterton and Lucas seized the excuse to drop the project to concentrate on manufacturing F3 Titans.

Ted had been commuting back and forth between Canada and the UK throughout this period, finally returning to the UK for good in 1969. He continued his involvement with full-scale car racing, working for MG and Lola among others. He designed an updated version of his Formula One engine and was involved with Colin Chapman in the testing of this engine, using a couple of test beds which he had established at Haddenham. A manufacturing agreement was secured with Coventry-Victor and a number of engines were in fact produced and used in actual races.

The engine was again very compact and light, weighing only some 230 pounds. However, it suffered from a series of failures in use which were eventually traced to a batch of flawed castings. Although this was put right, the engine's reputation suffered as a result and it never made the mark in Formula One that it might otherwise have done.

One venture which might have restored the credibility of the Martin F1 engine was the Monica project. This was a dream of the wealthy French industrialist Jean Tastevin, a director of a French company that manufactured railway rolling stock. He decided to create a French luxury sportscar named the Monica. Why the name? No prizes for guessing the name of Mrs Tastevin!

The initial plan was to use a de-tuned over-bored 3423 cc version of the Martin F1 engine, which produced some 240 BHP at 6,000 rpm. Discussions regarding the use of this engine led to an arrangement with no less a firm than Rolls Royce to manufacture the Monica powerplants to Ted's design. Ted was later to describe this to his motorsport colleagues as his proudest moment—from designing model engines for the Anchor Motor Co Ltd to designing full-scale high-performance engines for Rolls Royce was a huge step! It was also very lucrative—Ted was able to sell the Monica engine design at a premium price which basically left him financially set up for life.

However, the agreement was torn up when M Tastevin subsequently demanded that Rolls Royce guarantee the power output of each unit that they produced. Rolls Royce not unreasonably stated that they could do no such thing for an engine which they had not designed and developed themselves and that was that. Fortunately, Ted got to keep his money.

As matters turned out, the Martin-produced engines continued to display some residual reliability issues, and there were challenges too with respect to the maintenance of an adequate spares inventory which could not be overcome once Rolls Royce dropped out of the picture. Accordingly, M Tastevin eventually decided to go with 5.9 litre engines supplied by Chrysler and all but two of the very small number of Monicas which were produced used the latter engines. A few of the Monica engines built by Ted were used by British racing car drivers, notably in the Pip Danby Ford Escort V8 of 1970 as well as one or two others run by such drivers as Brian Cutting and Robin Grey.

Martin had been quite successful in a commercial sense from all of the above activities. The final step in the consolidation of his fortune was the sale of Alexander Engineering and the land on which it was located, leaving Ted well able to establish a very comfortable lifestyle at his latter-day residence at Thame in Oxfordshire. At one point he was notable for driving a pillar-box red Jaguar 3.8 Mk II as well as an E-Type Jag, and also had a large boat moored on the Thames near his residence.

Ted being Ted, there was no way that he could stay away from model engineering for long. In fact, he relished the challenge of model engineering, commenting that the required precision was far greater than that involved in his full-size racing productions! Accordingly, he established a well-equipped home workshop at his house in Thame. His interests became increasingly focused upon live steam and he became the guru of a sizeable group of enthusiasts for this facet of model engineering. His garden at Thame soon sported a very extensive 7-1/4 inch gauge steam railway layout and he stayed busy in the machine shop creating beautifully-made equipment to run on this track.

Despite this, he remained interested in the motorsport field as well. It's gratifying to be able to report that he did live long enough to see one of his Formula One engines not only restored to active service but placed front and centre in the winner's circle! This came about as a result of Alan Rennie spending five years creating a replica of the Pearce-Martin Lotus 35-based Formula One car using heads and blocks purchased from Ted himself. This superb re-creation had its debut race at Snetterton on June 7th, 2009, winning in Alan's hands after two faster rivals both retired. Ted must have been smiling.

Ted Martin remained active almost right to the end, and only his death on May 22nd, 2010 put an end to what can best be described as a lifelong obsession with precision engineering in so many manifestations. For a man without any formal qualifications, his achievements are nothing short of stunning. As Ted himself put it—"You couldn't do it today!" Still, Ted did do it, and did it well. We're all the better for his presence among us—thanks, mate!

I must pay tribute to my good friend and valued colleague Jim Woodside, who provided the bulk of the first-hand material upon which this page is based. In April 2004, Jim was privileged to actually meet with Ted Martin at his home in Thame, Oxfordshire and hear many details of his life's work from Ted's own lips. Fortunately, Jim made copious notes of the matters discussed and has been generous enough to share these with me to assist in the preparation of this tribute. It would be impossible to overstate the debt which we all owe to Jim for his foresight and generosity. Indeed, without Jim's contribution this story could not have been written.

Ian Russell of Rustler fame was also present at this meeting and retained a number of memories about matters not covered in Jim's notes. We're most grateful to Ian for generously sharing those recollections with us.

I'm also extremely grateful to Jim's friend Roy Pritchard of the Chester Model Flying Club, who worked for the Anchor Motor Co for many years right up to the closure of the company's doors in 1983. Roy was able to supply many details about the company which could only have been provided by someone such as himself who was intimately connected with the business for many years. We all owe very sincere thanks to Roy for his invaluable contribution.

Similarly, Ted's one-time aeromodelling associate Robin Parker, also a friend of Jim's, was able to provide a few more details about Ted's early life and his time in Chester, for which we're most grateful.

For the photos of Ted's garden railway at Thame, we thank Keith Wilson. Keith mentioned that he used scale-sized bricks for his engine shed, an accurately detailed turntable, and that his facing-point locks used "scale" nuts and bolts—for which there can be no higher praise. We completely agree.

![]()

This page designed to look best when using anything but IE!

Please submit all questions and comments to

[email protected]