David Stanger — Model Aviation Pioneer

Created: January 2007

At Hendon on the Sunday 19th of April, 1914, during the Olympia International Aero Exhibition, a canard biplane with a wingspan of seven feet weighing 10-3/4 pounds set a duration record of 51 seconds that was to stand unbroken until 1936 [1]. Both the aircraft and its power-plant were designed and built by Mr David Stanger. This record was established under the scrutiny of an official observer and timing group from the Royal Aero Club making it one of the earliest official records for model aircraft in that part of the world.

While 51 seconds may not seem like a long time, 18 years is. The trick, as such, is what constitutes an "Official" record for a "class", and who recognizes it. On the other side of the Atlantic, Langley's steam powered Aerodrome No 6 had flown for 105 seconds in 1896 [2]. This event lacked an accredited, impartial, official observer. Even if it had been so blessed, no international organization yet existed to collate attempts and regulate records. It was a simple case of "we have ours; they have theirs" and the record setters were probably more focused on the flight rather than its status in any record book. The achievement of these pioneers was not the record itself. It was the astonishing amount of creativity, experimentation and hard work that lay behind the achievements.

In the period from the first experiments in powered, heavier than air flight almost up until the outbreak of World War I in 1914, would-be aviators had virtually no option but to design and build both the airframe and the power plant. It is well documented how the Wright brothers designed the engine for their Wright Flyer, passing construction to their friend, Charlie Taylor [3]. In England, the young Geoffrey De Havilland needed to design an engine before starting design of his aeroplane, farming out actual construction to the Iris Car Company in 1909 [4]. About the same time, Stanger wrote to the newly founded AERO magazine describing the four cylinder, four-cycle V configuration engine he had designed, saying he believed it to be the smallest in the world [5].

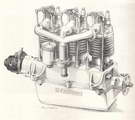

His letter, which appeared in the March 1, 1910 issue, described the engine as

weighing 5-1/2 pounds, complete with gravity fed carburettor and petrol tank. He estimated the power output as 1-1/4 hp at 1,300 rpm with a 30" diameter, 36" pitch prop. It had a 1.25" bore with a 1.5" stroke for a total displacement of 7.36 cuin. The engine was first fitted to a biplane with a wingspan of 8-1/2 feet. The elliptical dihedral of the lower wing (I'm sure he didn't call it that) is unusual for the day, indicating that he had his own ideas and was not just following the pack. The use of dihedral to augment lateral stability was not widely understood at the time, so it's highly likely that this contributed to his early successes as seen in the published photograph. The success of this model made David Stanger the first to person in England to achieve free, open air flights with a petrol engine powered model aircraft.

His letter, which appeared in the March 1, 1910 issue, described the engine as

weighing 5-1/2 pounds, complete with gravity fed carburettor and petrol tank. He estimated the power output as 1-1/4 hp at 1,300 rpm with a 30" diameter, 36" pitch prop. It had a 1.25" bore with a 1.5" stroke for a total displacement of 7.36 cuin. The engine was first fitted to a biplane with a wingspan of 8-1/2 feet. The elliptical dihedral of the lower wing (I'm sure he didn't call it that) is unusual for the day, indicating that he had his own ideas and was not just following the pack. The use of dihedral to augment lateral stability was not widely understood at the time, so it's highly likely that this contributed to his early successes as seen in the published photograph. The success of this model made David Stanger the first to person in England to achieve free, open air flights with a petrol engine powered model aircraft.

In my opinion, this achievement was more significant than the 1914 51 second flight. However it is the latter that is universally recorded in the literature [7][8][9][10] while with the singular exception of the Engine Collectors' Journal entry [6], his first achievements receive no mention.

Stanger's second engine weighed 42 oz, less than half the weight of the first. This should be no surprise as it was in effect, one-half of the V4. Both engines featured cam operated exhaust valves and automatic inlet valves. The steel cylinders had no fins; the only fins being those cast into the cast iron heads. The pistons were also cast iron, fitted with two rings each. The crankcase of both engines was cast in aluminium. The crankshaft of the V4 was fabricated, running in bronze bushes. The V2 featured a one piece crankshaft with big-end caps on the conrods [6]. In addition, Stanger made the sparking plugs and other ignition equipment for his engines.

Stanger's second engine weighed 42 oz, less than half the weight of the first. This should be no surprise as it was in effect, one-half of the V4. Both engines featured cam operated exhaust valves and automatic inlet valves. The steel cylinders had no fins; the only fins being those cast into the cast iron heads. The pistons were also cast iron, fitted with two rings each. The crankcase of both engines was cast in aluminium. The crankshaft of the V4 was fabricated, running in bronze bushes. The V2 featured a one piece crankshaft with big-end caps on the conrods [6]. In addition, Stanger made the sparking plugs and other ignition equipment for his engines.

The prestigious Flight magazine for April 25, 1914, carried some detail drawings of Savage's V2 powered canard and a photo of his new monoplane. This was designed for the original V4 engine and shows a distinct Blèriot influence—the major departure being a triangular truss fuselage. The Flight drawings could equally depict details of a full size aircraft of the period. Stanger was in effect, paralleling the other pioneers like Geoffrey De Havilland and Harry Hawker in their construction techniques. The main difference being the smaller size and the need for three-axis stability to replace that occasionally provided by a pilot.

The prestigious Flight magazine for April 25, 1914, carried some detail drawings of Savage's V2 powered canard and a photo of his new monoplane. This was designed for the original V4 engine and shows a distinct Blèriot influence—the major departure being a triangular truss fuselage. The Flight drawings could equally depict details of a full size aircraft of the period. Stanger was in effect, paralleling the other pioneers like Geoffrey De Havilland and Harry Hawker in their construction techniques. The main difference being the smaller size and the need for three-axis stability to replace that occasionally provided by a pilot.

Both the V2 powered canard pusher biplane and the V4 powered tractor monoplane were exhibited by Stanger at the 1914 Aero Show held at Olympia. A highlight of the show must have been the flying demonstrations Stanger conducted with both models (you can just see the delight expressed in the body language of the Bobby on the right in this photo). While both flew, it was the canard that was timed, out of sight at 51 seconds [11], thus establishing the Royal Aeronautical Society record that was to stand for the next 18 years. I can only assume visibility was poor as a 7 foot biplane does not generally become a dot in the distance after only 51 seconds!

Both the V2 powered canard pusher biplane and the V4 powered tractor monoplane were exhibited by Stanger at the 1914 Aero Show held at Olympia. A highlight of the show must have been the flying demonstrations Stanger conducted with both models (you can just see the delight expressed in the body language of the Bobby on the right in this photo). While both flew, it was the canard that was timed, out of sight at 51 seconds [11], thus establishing the Royal Aeronautical Society record that was to stand for the next 18 years. I can only assume visibility was poor as a 7 foot biplane does not generally become a dot in the distance after only 51 seconds!

|

|

|

David Stanger continued his experiments and designed at least three more types of model engine. In 1925 he designed and built a three cylinder in-line four-cycle engine. Unlike the V series, this engine had pushrod actuated inlet and exhaust valves and a twin-choke, float-chamber carburettor. This was followed in 1926 by a three cylinder in-line two stroke. He also built several single cylinder two-stroke engines. The smallest of these had a displacement of only 1cc. The single cylinder series of engines powered models with biplane and monoplane configurations [11].

Despite his obvious attraction to aviation, David Stanger was an automotive engineer, a fact evident in many aspects of his engine designs. In 1901 he had designed and built his own motor car, and in 1920, he built a 5 HP 2-stroke motor cycle engines that saw extensive use and was most successful in endurance trials. Although it was not all that unusual at the start of the 20th century, he not only built the engines, but also the lathe and micrometer they were made with. His sons Alfred and John both became professional engineers and also built many fine models.

Even though Stanger is remembered for his V configuration engines and his 1914 record, his other accomplishments deserve to be remembered as well. He was truly a pioneer model aviator and engine builder.

I am most indebted to Mr Tim Westcott for the photographs and other material that has made this page possible.

References:

| [1] | Greenhalgh, A: 50 Years of Model Aviation, The Model Engineer, December 1968 Exhibition Souvenir Handbook and Guide, Model and Allied Press, England, p47. |

| [2] | Heppenheimer, HP: First Flight, John Whiley & Sons Inc, New Jersey, p82. |

| [3] | ibid. p182. |

| [4] | De Havilland, G: Sky Fever, Airlife Publishing Ltd, UK, 1979, p52. |

| [5] | Nichol, RE: David Stanger's Pioneer Engines, Engine Collectors' Journal, Model Museum, Denver USA, Volume 7, No 2, Issue 32, June-July 1969, p2. |

| [6] | ibid. p3. |

| [7] | Camm, FJ: Model Aeroplane Handbook, George Newness Ltd, London, 1949, p16. |

| [8] | Smeed, V: Model Flying: The First Fifty Years, Argus Books, London, England 1987, p9. |

| [9] | Bowden, CE: Petrol Engined Model Aircraft, Percival Marshall & Co Ltd, London, undated (Preface text dated 1945), p7. |

| [10] | Fisher, OFW: Collectors' Guide to Model Aero Engines, Argus Books, Herts, England, 1977, p12. |

| [11] | Unsigned document dated 1967 now in the collection of Mr Tim Westcott (FRAeS). |

![]()

© Ronald A Chernich, 2007. All rights reserved. Please seek permission before reproducing this page.