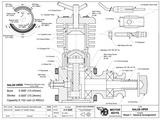

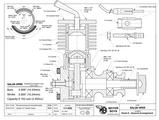

| Name | Nalon Viper | Designer | Norman A Long |

| Bore | 0.586: (14.43mm) | Stroke | 0.600" (15.24mm) |

| Type | Compression Ignition | Capacity | 2.492cc (.152 cuin) |

| Production run | very small | Country of Origin | UK |

| Photo by | Tug Wilson Eric Offen |

Year of manufacture | circa 1956-7 |

Background

The Nalon Viper was intended as a direct competitor to the Oliver Tiger, the latter being THE engine to have for free-flight, combat, and Team Race in Britain and elsewhere of the 1950's, if you could get one. Oliver's success derived from an excellent design, hand made to exacting standards, resulting is high demand and low volume. The Viper was intended to match the Oliver in terms of power and excellence. It certainly out distanced the Oliver in terms of hand crafting and limited availability.

The design and production were the work of Mr Norman A Long. This was far from his first model engine design and venture into model engine production, his earlier work being the highly efficient and noisy Yulon glow engines [1]. In 1948, Yulon Engineering Co of Birmingham had released the Yulon .30, a peripherally ported, updraft FRV engine of light weight, intended for control-line stunt when stunt was flown fast. This was followed by the Yulon .29 and .49. The final engine, the Eagle, appeared in 1951. This was not a happy period in Great Britain as model engine and equipment manufacturers found themselves subject to a backdated purchase tax.

This was the result of a 1948 decision of the Government to bring model aircraft parts and accessories, including "power units of all kinds" under Group 20 ("amusements") of the Purchase Tax Schedules [2]. The immediate effect of this was to impose a whopping 33-1/3% uplift on domestic over-the-counter sales. Previous to September 1948, kits and accessories of a constructional nature, while classified under "toys and games", were exempt from this tax. To fight this decision, an industry sub-committee was formed comprising Eddie Keil (Keil Kraft), Jack Ballard (ED), Arnold L Hardinge (Mills Bros), and Henry J Nicholls (Mercury Models Ltd). Legal advice to them indicated that it would be inadvisable to pay Purchase Tax allowing a test case to be raised. It was anticipated that the challenge would be successful and that a favorable decision would be backdated to January 1, 1949. The test case dragged on for almost two years, ultimately failing and thus claiming many British manufacturers who also had not paid the tax, nor made provision for it [3], Yulon included.

Norman Long however did not loose interest in model engines and decided to produce a high performance engine in the 2.5cc class. His first prototype was previewed by Peter Chinn in the October 1956 issue of Model Aircraft. Chinn stated that while the engine was a twin ball-race diesel like the Oliver Tiger, its design and detailed structural arrangement bore little resemblance to the Oliver beyond those points. If we add the design of the cylinder liner to this list, then I'd agree.

The first preproduction prototype Featured an Oliver-ported, cast iron ("Meenhite") liner with a close fitting, aluminum cooling jacket. Photos from the October and the November issues show a compression screw with a distinctive asymmetric Tommy-bar. When it appeared in October, the engine was un-named, Chinn mentioning that Long had invited him to provide a suitable one. In the November engine, Chinn dubbed it the Nalon Viper, saying the engine was essentially hand-built for those demanding top performance and that it was expected to sell at £9 retail, inclusive of purchase tax [4].

No more was heard until the July 1957 issue of Model Aircraft where a somewhat different variant of the Viper appeared in Chinn's Contest Motors column. The differences enumerated by Chinn were integral cooling fins on the cast-iron liner, flattened on the sides to assist close cowling, revised porting to reduce the transfer and exhaust, widened transfer port openings, venturi size increased from 7/32" to 1/4", and a new piston with lightening holes (where was not stated). Study of the photo shows a simpler "L" shaped compression screw in the thin alloy head, and the use of countersunk screws in place of the earlier 6BA Allen head machine screws. Chinn stated performance ranging from 0.385 bhp at 15,000 rpm, to 0.315 bhp at 16,000 rpm.

A first production run of 100 engines was planned, but it appears that few if any of these reached buyers' hands, making an original Viper a rare bird indeed. Being a bar-stock engine, reproductions have appeared from time to time. Sadly, original Vipers carry no markings making identification difficult, but we are pleased to say that the repros made by Motor Boy, Eric Offen, carry a stamp with the letters "EJO" on the bottom of the engine lug, helping buyers identify the provenance (very ethical, Eric—well done).

Description

The use of a fully machined crankcase allowed Long to keep weight down—Chinn stating that the later preproduction engines were lighter than an Oliver Mk III. The front housing carried a 7/8" OD by 3/8" ID rear bearing with seven balls; the front being 3/4" OD by 1/4" ID with six balls.

Being a Rear Rotary Valve (RRV) engine, this allowed the designer to employ a short, light shaft. The shaft was unhardened with a 1/4 BSF thread (26TPI) and a hard chromed 7/32" crankpin. The backplate had a short, pressed-in venturi and was threaded and counter-bored for a 6BA steel rotor pivot pin, locked externally by a 6BA nut allowing rotor end-play to be finely adjusted. The rotor was unbalanced and made initially from "Tufnol", although Chinn mentions some later experiments with nylon for the rotor.

Being a Rear Rotary Valve (RRV) engine, this allowed the designer to employ a short, light shaft. The shaft was unhardened with a 1/4 BSF thread (26TPI) and a hard chromed 7/32" crankpin. The backplate had a short, pressed-in venturi and was threaded and counter-bored for a 6BA steel rotor pivot pin, locked externally by a 6BA nut allowing rotor end-play to be finely adjusted. The rotor was unbalanced and made initially from "Tufnol", although Chinn mentions some later experiments with nylon for the rotor.

All crankcase faces were lapped for gasket free assembly (a simple process, compared to making gasket punches!) In a departure from other British engines of the period, Allen head 6BA machine screws were used throughout on the first model.

The NVA also used some unusual features. The spray bar was drilled 1/16" straight through (no regulating needle seat) and in place of the normal hole, or opposed holes for the fuel jet, Long cut the spray bar half way through at 45° in the venturi throat region. This I've not seen before (Johnson too used a slit, but not angled and not half-way through).

The surprises don't end there though. The "needle" has no point! The tip is just a blunt, squared-off face (see disassembled photo from Chinn's column in Model Airplane News [6]). When you think about it, this is exactly what is required to meter the fuel from the angled slit, the angle effectively providing a gradual increase in jet area. How well this will work is open to conjecture since I've never seen anything like it before, unless you count Duke Fox's angled flat "needle" used on the venerable Fox .35 which is not really the same thing. It's unfortunate that we have no record of the Viper being used in competition to see how well this arrangement would have held tune under race conditions.

The propdriver was secured by a split cone and was drilled to partly enclose the long, 7/16" tubular prop nut. This too followed Oliver and Cornell thoughts, allowing spare props to be fitted with spare prop nuts, already adjusted to the correct starting position, reducing lost time should a broken prop occur during a race.

The initial cylinder liner was machined from cast iron ("Meenhite"), and was positioned in the case by an exhaust flange. Exhaust ports were cut with a small diameter 3/32" slitting saw resulting in ports 3/16" wide internally, wider externally. This allowed the resultant trapezoidal inter-port posts to be drilled at an angle so that transfer opened shortly after the exhaust, as opposed to other peripherally ported engines of the time where the exhaust had to fully open before the transfer could start, significantly restricting the transfer duration if the exhaust was to be kept to a reasonable value and not open before expansion was near complete.

The transfers are drilled at an angle of 25° to the vertical. Photos of the prototypes show Oliver-style squared corners at the top edges of the passages, probably done by broaching. Chinn described the bore in the crankcase for the cylinder as tapered at the same angle as the transfer. This can only be maintained for a short distance before it must change to a lengthy parallel bore. Photos suggest that the external "entry" area of the transfer ports was enlarged somewhat on the first, finless prototype liners. Again from the photos, this practice was carried to the extreme on the later, integrally finned cylinder liners.

The piston, "Meenhite" cast iron again, was of the truncated cone variety. Long apparently tried combinations of hard chromed piston and au-natural liner, and vice versa. The wrist pin, 5/32" diameter was also hard chromed, drilled through, and fitted with end-pads, suggesting it was fully floating. With the size of the ports involved, this seems a risky decision as jamming, or rubbing in the exhaust would be likely (the engine was assembled so that the posts and hence transfer ports aligned with the cylinder hold-down screws).

As mentioned earlier, the first prototype reviewed by Chinn had a close fitting aluminum cooling jacket. Nine months later, he received a development of the engine with integral fins and a thin, flat aluminum head [5]. This engine also appears to have used countersunk screws throughout for assembly with a simple, bent "L" shaped compression screw, all of which would result in small but cumulative weight savings. Note that photos of the first prototype design exist showing both an asymmetric and symmetric "T" shaped Tommy-bar on the compression screw—I've never understood the idea behind the asymmetric type, but they sure help an engine look different!

Conclusion

Norman Long's first venture into model engine making produced a light weight stunt engine which for a time, was THE stunt engine in England. Economic circumstances brought the Yulon to a halt and it appears that the same was probably true for his second design. This is unfortunate as we never got to see what a Viper might do in capable hands on the Team Race circuit, paced against the Oliver Tigers, and later, the ETA 15 diesel. Today, its bar-stock nature makes it a good choice for the home engine builder wanting to try their hand at a twin ball race, "vintage" competition 2.5cc Team Race engine. Complete plans for both models (eight sheets) are available from us for AUS$45.00, with electronic delivery in pdf format ready for printing.

Norman Long's first venture into model engine making produced a light weight stunt engine which for a time, was THE stunt engine in England. Economic circumstances brought the Yulon to a halt and it appears that the same was probably true for his second design. This is unfortunate as we never got to see what a Viper might do in capable hands on the Team Race circuit, paced against the Oliver Tigers, and later, the ETA 15 diesel. Today, its bar-stock nature makes it a good choice for the home engine builder wanting to try their hand at a twin ball race, "vintage" competition 2.5cc Team Race engine. Complete plans for both models (eight sheets) are available from us for AUS$45.00, with electronic delivery in pdf format ready for printing.

References:

| [1] | Chinn, PGF: Mainly Motors, Model Aircraft, Volume 15, Number 184, Percival Marshall & Co Ltd, GB, Oct 1956, p360. |

| [2] | Russell, DA (ed): Editorial, Aeromodeller, Volume XIV, Number 157, February 1949, The Model Aeronautical Press Ltd, p138. |

| [3] | Rushbrooke, CS (ed): Editorial: Purchase Tax, Aeromodeller, Volume XVI, Number 180, January 1951, The Model Aeronautical Press Ltd, p11. |

| [4] | Chinn, PGF: Peter Chinn reviews some International 2.5's, Model Aircraft, Volume 15, Number 185, Percival Marshall & Co Ltd, GB, Nov 1956, p407. |

| [5] | Chinn, PGF: Contest Motors, Model Aircraft, Volume 16, Number 193, Percival Marshall & Co Ltd, GB, Oct 1956, p235. |

| [6] | Chinn, PGF: Foreign Notes, Model Airplane News, Volume 96, Number 4, Air Age Inc, NY, April 1978, p8 (photo). |

![]()