|

|

|

The following text appeared in Scale R/C Modeller, Vol 4, No 1, February 1978. Although now more than 30 years old, it continues to be spoken about and as copies of the article are hard to find, it is provided here, scanned and OCR'd to assist those thinking of similar projects. Readers should note that the plans mentioned in the text are no longer available. John's original prototype now resides for all to see in the Craftmanship Museum, Vista CA. The Museum also contains other, much larger multi cylinder engines made by John Thompson using commercial cylinder assemblies.

Ron Chernich, December 2009.

Pratt & Whitney Wasp Jr

From Scale R/C Modeller, Vol 4, No 1, February 1978.

Engine by John V Thompson.

Text by Bruce Robertson.

Photos by John Van Dyck.

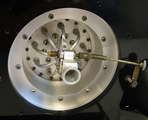

John Thompson's forte in the modeling field is superior-quality machining, of which his scale Pratt & Whitney Wasp Jr. is a perfect example. It took 18 months of machining, designing and plain old trial-and error to achieve the functional power plant shown here. Developed around nine Cox .049s (Baby Bees fortunately, or the cost would be staggering), the scale Wasp Jr. uses reed valves for fuel flow. Gearing is via a single planetary gear (ratio 2.1:1) driving nine secondary gears. Originally, a 1:1 ratio was tried, with poor results.

Other interesting features of the engine are a functional ignition system for starting (no, you don't need nine separate glo clips). The original Cox glo-plugs are retained for convenience, and the whole thing is ingeniously hidden under bits and pieces of plastic from Williams Bros. dummy engines.

No doubt all you "doubting Thomases" out there are already shaking your heads in disbelief. It looks great but . . . does it run? To which we retort: would a man spend all that time making something that wouldn't work? Mr. Thompson's engine is rated as a .45, and will swing an 18-4 prop at 10,000 rpm. Try that on your Enya, K&B or Super Tigre some time!

Admittedly, there are a few minor problems (other than spending a year and a half building the engine!). True to scale, the engine doesn't like to start in the vertical position. The bottom cylinders will naturally flood, since they all feed from one master carburetor. Actually, this was typical of the full-scale radials, which would collect oil and fuel on the gravity side very quickly. It took a deft hand to get a 7- or 9-cylinder Wasp to run smoothly at all power settings, and it took a macho mechanic to keep the bottom plugs from fouling.

Mr. Thompson handily solves this problem by simply starting the engine in a horizontal position (prop shaft pointed straight up). That way, all the cylinders get an equal shot of fuel. Being a minor masochist machinist, John took the time to make his own throttleable carburetor. For those who want to shave a few hours off the time needed to build the Wasp Jr., the use of a Perry carb is advised. The throttle response is exceptional, as might be expected from an engine which always has one cylinder firing. It goes without saying that the power plant is virtually vibration less, and you can almost hold it in your hand at idle.

Since there's a complete ignition harness designed into the Wasp, all nine plugs are simultaneously lit when the battery is attached (that's one big battery, too, for the plugs draw 36 amps!). Hand starting is no problem, and the engine generally starts on the first flip. Unlike the full-size Wasp Jr., which had a sequential firing arrangement, the replica engine has all nine pistons going to Top Dead Center simultaneously. There's no reason why Mr. Thompson's concepts couldn't be applied successfully to a seven cylinder Gnome, or even a Double Wasp.

It would be a mistake to try to incorporate this engine in anything other than a 2" = l' airframe. The scale P&W weighs about twice as much as a normal 040, but who has ever built a bipe that didn't need a bunch of nose weight anyway? The engine wasn't designed as an odd-ball showpiece, but it is intended to fly an RIC model. With its ability to swing a big prop, how fantastic it would be on the nose of a Stearman. There's even the nicety of a scale functional exhaust collector ring (constructed from four fiberglass sections).

For those who have the lathes and milling machines required for such a project, Mr. Thompson is making available a five-sheet set of machinist's drawings. There is also a lengthy set of step-by-step notes on the fabrication of the Wasp Jr., and a detailed parts list and addresses of manufacturers and suppliers. The whole thing is available from Mr. Thompson for $25.00 (425 E. McKellips Rd., Lot #62, Tempe, AZ 85203).

Scale R/C Modeler is proud to recognize Mr. Thompson's superior achievement. It's truly a labor of love to even begin such a project, and to pull it off successfully is nothing short of a major triumph. Now that all the hard work has been done and all the bugs ironed out, you might want to have your own Wasp Jr. One thing for sure, having an operational scale engine' hung on the firewall of that next project just has to blow the judges' (and spectators') minds. While you're at it, why not go whole hog and build three of them for a 2" scale Ford Trimotor?!

Some closing thoughts from your editor: With very few exceptions, magazines exist to make money for their publishers. To do this, they need to provide something their readers value, otherwise no readers and no profit! Now call me an old cynic, but given all this, I expect them to lean towards the "gosh-wow" side of reality more often than not.

I have no doubt that John Tohmpson achieved a measure of success with his designs, all of which show fine craftsmanship. I also have no doubt that the magazine editors honestly admired his achievement and saw promoting the idea that you too could build your own as one of the things that sells magazines. Besides, very few readers of the article would have the real capability to carry out the work, so the editors could safely put a high gloss on the piece with little chance of being "found out". And what's wrong with letting people dream a little? Ok, back to reality. Let's consider a couple of little points.

- A Cox cylinder runs hot. Hidden behind a fake plastic cylinder, it is not going to get a lot of cooling. And don't think you could hide a fan of some kind in there. Lastly, a hot cylinder radiates and applying heat-resistant paint does not make the plastic heat-resistant!

- The spider fuel distribution is always going to be a less than ideal compromise and some cylinders are always going to run rich. I do admire the honesty regarding starting the engine horizontally. Now think how practical that would be in a delicate scale model.

- There is an inconsistency in the text. In the paragraph talking about the starting position, the text states that the throttle response is exceptional because the engine "always has one cylinder firing". The next paragraph however correctly says "the replica engine has all nine pistons going to Top Dead Center simultaneously". Nobody with any serious engineering background ever edited this article.

I'm not saying it is impractical, it's not as John and many others have aptly demonstrated. But it's not as easy as the article might suggest. And if the intent is to hang it in the front of a scale, scratch-built model, the last thing you want is an unreliable or difficult to operate power-plant. Looks great though, but so does a Hodgson.

![]()