The MEC 1.2cc Mk IV Diesel

by Adrian Duncan

|

|

|

| Click on images to view larger picture. | ||

Here we take the first-ever in-depth look at one of the more obscure model diesel engines to be produced in Britain during the early post-war era. The neat little ultra-lightweight MEC 1.2 cc diesel which is the focus of this article has hitherto been almost completely undocumented. All we have to go on are a few advertisements, a few brief references and an actual example which is fortuitously available for evaluation.

This being the case, we wish to make it clear at the outset that a significant proportion of what follows must be viewed as no more than informed speculation. Should further facts come to light in the future, we will of course amend this article as necessary, giving full credit to our sources.

As always, research of this nature is quite impossible without the help of others. In this instance I have to thank my good friend and valued colleague Kevin Richards not only for making available the fine example of the ultra-rare engine upon which this article is based but also for digging out much of the related advertising material. Without Kevin's help, I could never have even begun this analysis, let alone completed it. Thanks, mate!

OK, armed with the relatively sparse resources at our disposal, let's see how we get on.

Background

The MEC 1.2 cc Mk IV diesel was produced in very small numbers in London, England over a period of approximately fourteen months beginning in May 1948. It appears to have been a small-scale artisan workshop production rather than a mass-produced item like most of its competition.

The engine was mentioned in the 1949 second edition of Col CE Bowden's book Diesel Model Engines and was included in the technical tables published as appendices to Ron Warring's 1949 book, Miniature Aero Motors. However, Warring did not include it in his table of model diesel engines for 1948/1951 which was published in Model Aircraft in 1951. Presumably he felt that the engine had failed to make a sufficient mark to be worthy of notice!

Warring's views in the above regard most likely stemmed from the fact that distribution of the little MEC seems to have been restricted to a relatively small area in North London and was in fact apparently focused for the most part upon a single location. As far as can be ascertained today, the main retail sales outlet for the engine was the North London firm of Premier Aeromodel Supplies Ltd.

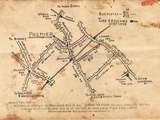

Premier Aeromodel Supplies was one of Britain's pioneering model supply houses. The firm had been trading since 1929 from a location at 2A Hornsey Rise, a little to the north of Islington. The precise location was the north-west corner of the intersection of Hornsey Rise and Hazellville Road. This location has been re-developed since WW2 and is now incorporated into the area of Elthorne Park.

Premier Aeromodel Supplies were both manufacturers and retailers—in addition to their retail premises at Hornsey Rise, they maintained a separate manufacturing facility known as Hill View Works which was located on East End Road in nearby East Finchley. Both kits and accessories were manufactured at this location. The company was early in the mail order field, and their pre-WW2 catalogues were remarkably lavish affairs, complete with a hand-drawn map showing how to get to their retail location!

The Premier company continued trading throughout WW2, as demonstrated by their periodic placement of advertisements during that unhappy period in which modelling activity was highly restricted. The conclusion of hostilities found them still very much in business at their pre-war address. Their main focus was the supply of kits and accessories of their own manufacture, but they also seem to have offered a wide range of goods from other sources.

At some point prior to August of 1947 Premier became a participant in what appears to have been some kind of a consortium of model shops at four North London locations. This consortium traded under the collective name of Model & Air Sports Ltd., with branches at 39 Parkway, Camden Town (managed by C.A. "Rip" Rippon of future Ripmax fame); 37 Upper Street, Islington; and 132 Green Lanes, Palmers Green as well as the Premier Aeromodels address at 2A Hornsey Rise.

It's a little odd to note the close proximity of these locations to one another. Upper Street in Islington is no great distance from either Hornsey Rise or Parkway (Camden Town). Even Palmers Green is only a little to the north of Hornsey Rise and the East End Road manufactory in East Finchley is only a short distance to the north-west. It's possible to draw a circle of less than seven miles diameter on a map which contains all four retail locations as well as the Premier manufactory at East Finchley!

Such a concentration of similarly-focused retail outlets in a relatively small geographic area does not at first glance appear to make much sense for a single business entity. One actually gets a strong impression that this was a case of a group of originally-independent model shops in close proximity to one another getting together to work co-operatively rather than in a state of mutual competition in which at least some of them must surely have gone under.

The Upper Street address in Islington was apparently the central location of Model & Air Sports' mail order service. Membership in the consortium evidently did not require the participants to surrender their previous identities, since Premier Aeromodels continued to advertise under their own name throughout, sometimes placing their advertisements directly beside those of Model & Air Sports Ltd. However, in doing so they invariably used the East End Road address of their manufacturing facility in East Finchley—their retail outlet at 2A Hornsey Rise apparently operated under the Model & Air Sports Ltd. banner during this period. It appears that they were presenting themselves as manufacturers rather than retailers at the time.

At this late date, it's no longer possible to sort out the respective roles of Model & Air Sports and Premier Aeromodels in the production and marketing of the MEC diesel. All that can be said is that the engine was advertised by both entities during its short production life and that Premier Aeromodels appears to have been the most active and persistent individual member of the Model & Air Sports consortium in promoting the little MEC

There are two unsubstantiated possibilities regarding the way in which the businesses concerned became involved with the marketing of the MEC engine. The first (and in my personal view most likely) is that the engine was developed by some local model engineering type working on his own who then approached either Premier Aeromodels or Model & Air Sports with samples of his fully-developed design and arranged a marketing deal with them. If he was an individual working alone in the proverbial "garden shed", as seems not unlikely, the single sales outlet would likely be all that his production capabilities could support.

There is some support for this theory in the form of the engine's name—the MEC designation bore no relationship to the names of the two business entities which marketed the engine. Moreover, almost from the beginning the engine was referred to as the MEC 1.2 cc Mk IV diesel. This clearly implies that by rights there should have been preceding Mk I, Mk II and Mk III models, but we can find no firm evidence that such models were ever marketed, at least in those terms.

This however by no means proves that they never existed! It's perfectly consistent with the above theory to suppose that the unknown designer (whoever he was) had gone through three previous iterations of the design before finally settling on the fourth and final version as being worthy of small-scale series manufacture and approaching the local model trade to secure a marketing agreement for that variant.

There is of course the alternative possibility that Premier Aeromodels or Model & Air Sports themselves conceived the notion of having the engine produced for them and approached the unknown maker to arrange for this to be done to their specifications. However, this is surely inconsistent with the fact that they did not apply either of their own proprietary names to the engine. Moreover, such a move into the engine manufacturing field would represent a major shift in focus from Premier's previous interests, which had generally been connected with the supply of kits, plans, materials and accessories. It's hard to see why such a relatively small company would choose to go head to head with the ever-increasing number of established engine manufacturers which were then supplying the needs of British modellers.

Furthermore, the above possibility does not explain the apparent anomaly of the Mk IV designation and the seeming absence from the market of the three implied earlier models. Overall, some form of external "persuasion" seems far more likely. It's highly doubtful that we'll ever know—most or all of the principals are surely long departed after the passage of over 60 years.

Regardless, the fact that production of the engine appears to have been tailored towards its sale through a single North London retail consortium doubtless explains its extreme rarity today. With such a localized marketing history, it's only to be expected that very few of these engines would in fact have been made and sold, and the apparent present-day scarcity of surviving examples backs this up—a mixture of rocking horse droppings and hen's teeth comes to mind! The near-mint example that I'm lucky enough to have on hand for evaluation is the only example that I've ever seen in the metal, and my good mate Kevin Richards (from whom I obtained the engine) has only seen two examples (including this one) in over 40 years of collecting! But there must be a few more of them out there; keep looking!

It has not been possible to identify the designer and/or maker of the MEC 1.2 Mk IV—in fact, we don't even know what the letters MEC stand for! The designer's initials, perhaps.... or Model Engine Somethingorother? At this late stage, we accept the likelihood that this information has been irretrievably lost through the passage of time, but if by chance anyone out there knows more than we do, we'd be absolutely delighted to hear from you! Our sole motivation in publishing these articles is to encourage the capture and preservation of as much model engine history as possible while the smallest crack remains open in the steadily-closing window of opportunity. All contributions openly and gratefully acknowledged.

Production History

Thanks in large part to some excellent work by Kevin Richards, we have access to a number of advertisements for the MEC diesel. These allow us to trace the production history of the engine with some confidence.

The earliest advertisement that we can find is a placement by Model & Air Sports in the May 1948 issue of Aeromodeller. Interestingly, an advertisement for Premier Aeromodels appeared directly alongside this placement, although the address used in that advertisement was the East End Road manufactory in East Finchley, presumably to avoid duplication. It appears that as of that date Premier Aeromodels had retreated into the role of manufacturer, with their retail store at 2A Hornsey Rise being operated at that time under the Model & Air Sports banner. If so, this arrangement was not destined to last.

The Model & Air Sports advertisement was an "announcement" of the MEC engine, thus dating its introduction pretty closely to May 1948. Interestingly, the displacement of the engine was given as 1.1 cc rather than the 1.2 cc quoted later. The cited weight too was slightly higher at 1.7 ounces. It's accordingly possible that this was one of the earlier "marks" under which the engine's later Mk IV title suggests that it was produced.

The advertisement claimed that the engine had survived a 15 minute test at 15,000 rpm (presumably using a flywheel) and would sustain 7,000 rpm with a 9 inch prop, likely a 9x4 if later recommendations are anything to go by. The quoted price was �4 4s 0d. Mail order sales were invited, or one could call at any of the consortium's four listed retail locations.

If the above advertisement was indeed for an earlier mark of the engine, it didn't last long—by August of 1948 we find an advertisement in Model Aircraft (again placed by Model & Air Sports) specifically touting the "latest" Mk IV version of the MEC diesel. Readers were invited to visit the Model & Air Sports stand at the 1948 Model Engineer Exhibition, where both the Mk IV version of the MEC diesel and the latest kits from Premier Aeromodels would be on display. CA "Rip" Rippon was among the "stars" scheduled to staff the exhibit.

In the October 1948 issue of Aeromodeller we find Premier Aeromodels advertising the "latest" MEC Mk IV under their own name for the first time—possibly a few cracks were developing in the Model & Air Sports consortium at this point! The displacement was now stated to be 1.2 cc and the weight was claimed to be down to only 1.5 ounces. These figures seem to imply that the version announced in May 1948 by Model & Air Sports had indeed been an earlier version. The price too had been reduced to �3 15s 0d. Premier were still using the East End Road address in East Finchley as of this date.

This advertisement provides some important additional information by specifically claiming that the engines were "individually built, not mass produced". This clearly implies an artisan workshop level of production in accordance with our earlier speculation. The engines were stated to be "produced entirely of first-grade bar materials", i.e., no castings were employed. An examination of the engine confirms this latter statement.

Model & Air Sports were back in the saddle in December of 1948 with their own advertisement in Model Aircraft for the MEC Mk IV. The basic information on the engine was the same as that which had appeared in the October placement by Premier Aeromodels, and the price too was unchanged. This advertisement did however include the claim that the engine was "indisputably above all comers in the field for power (to weight?) ratio". Interestingly, inquiries were invited at only the Upper Street address—no mention of the Premier location! This may be a further sign that the consortium was in the process of disintegrating—the "partners" had begun advertising in competition with each other!

Another rather obscure point about this advertisement was the note that the engine was "adaptable to inverted or upright running". Given the fact that the carburettor assembly was entirely soldered together (as we shall see) and was set up as supplied for upright running only, it's hard to see how this claim could be in any way substantiated.

During the first half of 1949 Premier Aeromodels went back to advertising under their own name from their original Hornsey Rise address—the consortium had evidently fallen apart and no more was to be heard of it. "Rip" Rippon joined forces with Max Coote in 1949 to form the famous Ripmax company, which initially traded from Rippon's 39 Parkway, Camden Town location. The company went from strength to strength and remains very much in business today (2010) as the UK's largest distributor of R/C models and accessories.

Premier's June 1949 placement in Aeromodeller made no mention of the MEC, but that model did reappear in their July 1949 Aeromodeller advertisement, although it was by then playing second fiddle to a number of other products which were more prominently featured. As far as I am aware, this was the final advertised appearance of the engine. It actually appears likely that production had ceased by that time and they were merely selling off unsold examples.

The above summary strongly implies that the MEC was a small-scale artisan production, for which one would expect production figures to be relatively low. In addition, the engine was only in production for just over a year and was sold within a very small geographic area. These factors certainly explain the relative scarcity of surviving examples today. Probably only a few hundred at most were made in total.

Having reviewed the above rather scanty background material, let's now take full advantage of the fact that we have a fine example of this engine available for direct examination.

Description

We have no information whatsoever regarding the initial form in which the MEC was offered for sale. We previously noted that the introductory advertisement of May 1948 referred to a displacement of only 1.1 cc along with a weight of 1.7 ounces. These figures are slightly at variance with those subsequently quoted (and checked) for the Mk IV version which forms our main subject. We can only assume that the original model was an earlier variant, perhaps the Mk III.

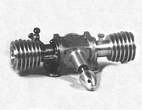

The MEC 1.2 cc Mk IV diesel which was first announced by that name in August of 1948 was a basically conventional sideport diesel of its day, mainly distinguished by its remarkably compact dimensions and light weight for its displacement as well as the fact that it was arranged exclusively for radial mounting. This form of mounting was actually enjoying something of a vogue in Britain at the time, with makers such as Aerol Engineering of Elfin fame, International Model Aircraft with their FROG range, Majesco with their little 0.735 cc Mite and the "K" Model Engineering Co. all offering popular radially-mounted models as of 1948/49. British aeromodellers later came down quite firmly in favor of beam mounting as the accepted standard, but this was not true at the time in question.

One's initial impression upon first encountering the MEC is that there's no way that it could possibly pack 1.2 cc into its compact ultra-light structure! By comparison with models of similar displacement from other makers, the engine looks positively minute! However, a check of the illustrated example confirms the cited displacement figure.

The makers claimed a weight of only 1.5 ounces for the engine, and this weight is more or less correct if one removes the hang tank supplied with the unit. However, with the tank in place, mine weighs in at 55 gm (1.94 ounces) all complete. This is still well below the weights of any of its direct competitors, including several of somewhat lesser displacement. The only competing model to marginally beat this figure was the Mk II AMCO .87 diesel at 1.75 ounces, but that engine also had a 28% smaller displacement. None of the other models in the 1.2 cc neighborhood came close.

Unusually for a time when long-stroke designs still predominated in Britain, the MEC featured almost "square" internal geometry. Bore and stroke were 0.450 in. (11.43 mm) and 0.460 in. (11.68 mm) respectively for a calculated displacement of almost exactly 1.20 cc (0.073 cuin) as claimed. The illustrated example checks out at almost exactly these figures, the very small departures being consistent with normal production tolerances.

To modern eyes, the 1.2 cc displacement seems a little offside. However, engines having what we would consider today to be "orphan" displacements such as this were by no means uncommon in the late 1940's and even into the 1950's. At the time of which we are speaking, the issue of displacements for competition classes was far from standardized—for example, the "magic" displacement of 2.5 cc (0.15 cuin) had not yet been adopted by the FAI for International competition.

Quite apart from this, aeromodelling was still far more of a hobby than a sport in those far-off days and the vast majority of modellers were not as interested in all-out competition as they were in simply enjoying their aeromodelling activities and gaining experience using dependable equipment. For these purposes, no particular displacement really had much of an edge over another. The only issues were what size of model was desired and whether or not a given engine could do the job of flying that model to the standard required while giving the operator a minimum of trouble in doing so.

Engines of 1.2 cc displacement or thereabouts were not at all uncommon in Britain at this time—the famous London-made Mills 1.3 Mk I model of late 1946 had in fact been Britain's first successful commercial diesel and was in widespread use in its Series 2 form by 1948. The Foursome 1.2 cc diesel from Brighton was also on the market and drew a fair bit of attention, although it was no match for the Mills in performance terms and was never produced in anything like comparable quantities. There was also the infamous Milford Mite 1.4 cc model from just up the road in Harrow, a good example of which actually outperformed the Mk I Mills, as conclusively demonstrated in our published comparison elsewhere on this site. Finally, the short-lived MS 1.24 cc model from Newcastle put in a brief appearance more or less concurrently with the MEC offering.

Seen in this 1948 context, there was actually nothing at all extraordinary about Model & Air Sports or Premier Aeromodel Supplies marketing what was presumably intended to be their "exclusive" in-store model with a displacement of 1.2 cc. In all probability the designer(s) simply established the physical design parameters in terms of target weight and physical size and then pushed the displacement up to the limit allowed by those parameters, thus maximizing the potential power/weight ratio. Indeed, it appears that the major design objective with this engine was to maximize that ratio.

The price of the MEC was more or less in line with that of its competition. Although its introductory price of �4 4s 0d was a little above the average, we saw earlier that the figure was quickly reduced to �3 15s 0d. This was well above the �2 12s 6d cost of the Foursome 1.2 cc from Brighton, but substantially undercut the Mills 1.3 at �4 15s 0d, the M.S. 1.24 at �4 15s 6d and the Milford Mite Mk III at �4 4s 0d. The MEC even undercut some smaller competing models such as the contemporary 1 cc sideport Kemp Eagle Mk I, which sold at the time for �3 18s 6d.

However, the Mills benefited from being the only one of these models to enjoy a truly national distribution network backed by an adequate production capacity, and hence in sales terms it was no contest—the Mills almost certainly outsold all of the rest put together over the same period! Certainly, it was the only one of them to survive.

In terms of its physical construction, a present-day inspection of the MEC 1.2 cc reveals that the basic structure is very simple indeed. As advertised, no castings are used at any point, the entire engine being machined from bar stock.

The thin-walled steel cylinder has integrally-turned cooling fins and is attached to the aluminium alloy crankcase with four 8 BA screws which pass through the corners of a square cylinder base flange. These corners actually appear to me to represent the most vulnerable points in the engine's structural integrity, since they are relatively insubstantial and look as if a really hard blow to the cylinder could possibly fracture them. Otherwise, the unit appears to be quite sturdy, with adequate strength where it's most needed.

The cylinder base has no locating spigot, and accordingly it is laterally located solely by the four screws through the corners of the mounting flange—a somewhat questionable arrangement in my view, although the screws are closely fitted to their holes and the threads in the case are well formed. A gasket is used to ensure a seal. A turned aluminium alloy cylinder head is secured to the top of the cylinder with four more screws, and an L-shaped steel compression screw is mounted in the head.

The crankcase is machined all over and has clearly been hogged out from the solid rather than cast. The main bearing is formed integrally with the crankcase and is fitted with a pressed-in steel bushing. The backplate is a conventional screw-in item which incorporates a large-diameter flange at its outer edge. A ring of holes having a 1 in. pitch circle diameter is drilled in this flange to provide for radial mounting of the engine. It is of course essential that this unit be really well tightened prior to use, since starting torque arising from the necessary flick-over tends to unscrew the engine from the backplate. Once running, however, the engine's torque will tend to tighten the backplate.

It has to be said at this point that the engine is not ideally set up for radial mounting, especially if the standard hang tank is to be used. The front of the tank is very close to the rear face of the mounting ring, so one would either have to use a very thin mounting firewall or provide a fairly large cutaway in the firewall to create sufficient clearance for the tank.

Cylinder porting is more or less conventional for a late 1940's sideport diesel. Both the induction and transfer ports are simple round holes of reasonably generous size, while the exhaust chores are handled by two oval ports of quite adequate dimensions, one on each side. Unusually for an engine of this layout, the single transfer port overlaps the exhaust almost (but not quite) completely. It is fed through a bypass passage formed by soldering a narrow brass channel to the exterior of the cylinder below the cooling fins, very much along the lines of the contemporary E.D. 2 cc models. This bypass passage is fed at its lower end by another hole which communicates with the lower crankcase by way of a cut-away machined into the front of the crankcase interior.

A steel connecting rod of generous proportions is used in conjunction with a steel piston and one-piece steel crankshaft. The rod appears to have been hand-filed from a piece of flat steel plate. Bearing fits at both ends are excellent. This "all-steel" construction was a fashionable specification among British designers of the period, but it did not stand the test of time—the undesirability of the "hard-on-hard" approach was soon appreciated and progressively abandoned.

The fact that the induction and transfer ports are round holes which are located fore and aft in the cylinder means that the 0.100 in. dia. gudgeon pin has to be restrained from movement in the piston bosses to avoid fouling the ports. This appears to have been accomplished by swaging the ends of the pin following installation—the associated punch marks in the gudgeon pin centres are very obvious.

The one-piece steel crankshaft has an unbalanced plain disc crankweb. It has two flats machined into it immediately forward of the 0.220 in. dia. main bearing journal, and the aluminium alloy prop driver engages very snugly with these flats by means of a milled channel at the rear, very much along the lines of the contemporary Ace 0.5 cc unit. The prop mounting arrangements are completed by the addition of a neat aluminium alloy spinner nut. A major criticism at this point is the fact that the length of the 2 BA prop mounting thread is far too short to accommodate the 8 and 9 inch diameter props which were recommended for this engine. It would be absolutely necessary to use a sleeve nut to fit such airscrews unless the hubs were significantly thinned.

The intake tube is of brass and is soldered to the rear of the cylinder. A very thick spraybar is soldered into this intake tube and is drilled through transversely along the intake alignment at slightly less than intake I/D. This form of assembly naturally means that the hang tank provided with the engine can only be used with the unit mounted in an upright configuration, as noted earlier.

An odd feature which should be mentioned at this point is the presence of a tiny pin-hole in the right-hand side of the intake tube on the engine side of the needle valve assembly. This may be seen in the right side view of the engine presented earlier. Its effect is to induce an air bleed when the open end of the intake is closed for choking. Perhaps it was intended to minimize the possibility of over-choking and flooding.

The orifice on the fuel supply side of the spraybar is very small and acts as a surface jet within the constriction created by the transverse hole in the spraybar. The larger hole on the needle side is tapped to accept the externally-threaded needle, which is tensioned by a coil spring.

The very neat turned aluminium tank top is centrally threaded and screws onto an externally threaded portion of the spraybar on the fuel supply side. The brass pickup tube is also internally threaded and screws onto the spraybar beneath the tank top. Finally, the turned aluminium tank bowl itself is secured by a screw which locates in the lower end of the internally threaded brass fuel pickup tube. A side hole drilled through the wall of the pickup tube draws fuel from the tank. There is no cut-out provided.

If it is desired to use the engine with a tank other than that supplied, all that is required is to remove the retaining screw and the tank bowl and connect the engine to a separate tank using fuel tubing slipped over the pickup tube far enough to block the side hole in that component.

The finishing touch is the application of a black engine enamel finish to the cylinder and intake tube. The result is a remarkably lightweight and compact little power unit which looks well able to give good service. All fits are up to the very best standards throughout.

The MEC In Print

We saw earlier that the MEC was mentioned in the 1949 second edition of Col. Bowden's book, Diesel Model Engines. Since this brief summary appears to constitute the only description of the engine ever to appear in the contemporary modelling media, it seems worth quoting in full:

The 1.2 cc MEC is a very light motor weighing only 1-1/2 ounces. The makers claim it weighs one-third less than the lightest of its approximate cc and can be used on sailplanes without any other alteration than for fixing. The engine has a high power-weight ratio. It has even flown a lightly-loaded 7 ft. span model with success. Only MEC fuel is supposed to be used with this motor. The bore is 0.450 in., stroke 0.460 in. Height 1-7/8 in., length 3-1/8 in., width 3/4 in., diameter of bulkhead fixing flange 1-1/4 in.

Unfortunately, Bowden did not supply details of the mysterious fuel—perhaps the makers were not forthcoming on this subject. It's interesting to note however that the makers were definitely touting the extremely light weight of the engine, which made it suitable for use in models which were originally designed as sailplanes and (presumably) for rubber power. Readers of our companion article on the Kemp (later K) Hawk will recall that the makers of that engine claimed similar advantages in their advertising.

The M.E.C was also included in the technical tables which appeared as appendices in Ron Warring's 1949 book Miniature Aero Motors. However, these tables are confined to technical data only and add nothing to our knowledge of the engine as summarized above—they merely confirm our observations (and vice versa!). There was no reference to the engine in Warring's text.

Apart from a cameo appearance on page 120 of Mike Clanford's useful but often unreliable book, A-Z of Model Engines, and a one-line mention on page 41 of OFW Fisher's book, Collector's Guide to Model Aero Engines, the references above appear to constitute the sum total of the MEC 1.2 cc diesel's appearances in the modelling media prior to the appearance of the present article. The engine was never the subject of a published test, but we can do something about that!

The MEC On Test

As we see it, the fact that we are fortunate enough to have a fine example of the MEC on hand effectively imposes a duty to subject it to a comparative test to see how it compared with other contemporary offerings. If we don't do so, who will?

For comparative purposes, we can do no better than put the MEC up against what must surely have been the contemporary standard of comparison—the somewhat larger, more expensive and far heavier Mills 1.3 Mk I Series II which was in production up to May of 1948 and was thus contemporary with the MEC at the time when it first appeared. For the sake of interest, we'll also add the contemporary Kemp Eagle Mk I sideport model to the list, since that engine too was marketed for the most part in the London area at a comparable price and hence must have represented credible competition to the MEC despite its slight displacement disadvantage. All three models are sideport designs, so the playing field appears about as level as we can make it.

The recommended airscrews for the MEC as recorded by Ron Warring were a 9x4 for free flight and an 8x6 for control line. It was thus clear that these sizes would have to be included in the tests. I had earlier figures for both the Mills and the Milford Mite Mk III using these and other airscrews, but for the sake of maintaining a direct comparison I repeated the tests with the Mills alongside those of the other two engines using the same props and the same fuel on the same day. The Mills actually improved slightly upon its earlier performance, highlighting the necessity of repeating the tests.

The first task was to make up a radial mounting for the MEC I also had to come up with a suitable 2 BA sleeve nut to allow for testing the anticipated prop sizes. These tasks accomplished, the testing could begin. The fact that all three tested engines have built-on fuel tanks really did make testing very convenient—I have to echo Lawrence Sparey's often-repeated comment in that regard!

For the tests, I used a quite "oily" fuel with 2 � % nitrate equivalent. This level of nitrate is undoubtedly not necessary for these low-speed engines, but it does reduce the compression requirements somewhat and may help to minimize stresses in the 60-year old components.

I started off with the 9x4 prop on the MEC, setting the compression and needle valve controls by "feel" and guesswork respectively. After the tank was filled and a finger choke was given, I injected a small prime to offset the storage oil that remained in the engine, and two flicks later it was running! Amazing—after who knows how many years resting in collections?

It turned out that a prime was pretty much essential for starting—for some reason, choking alone doesn't seem to do the trick. Perhaps it's that little air-bleed hole in the intake, however if the engine was primed, it invariably started in one or two flicks. Really user-friendly! The compression could be left alone at its running setting, but the engine picked up better if the needle was pulled half a turn for restarts. Once the engine was running, it could immediately be closed down half a turn to its running setting. This proved to be around 3-1/2 turns from fully closed.

The tank supplied with the MEC looks pretty small, and indeed its capacity is rather marginal for the engine's fuel consumption. A full tank gives a full power run of only 40 seconds, including warm-up. This of course is adequate for sport free flight use, and the fact that the engine requires minimal fiddling once running means that there would be little delay between a start and the actual launch.

This example appears to have received little use, and it's still quite tight. The steel piston actually has a tendency to tighten very slightly in the bore when the engine is hot—I think that an hour or so of running would be necessary to cure this. I didn't feel like putting too much time on the engine given that I wasn't planning to fly it, so I contented myself with taking readings during the first 30 seconds of running before the tightening began and the engine slowed somewhat. The readings taken therefore represent the minimum performance of which this engine is capable—if well freed up, there's no doubt that it would beat these figures.

Even so, they aren't that bad! The MEC turned a Taipan 9x4 at 6,500 rpm, a little ahead of the 6,400 rpm managed by the Mills on the day and well up on the 5,800 rpm of the Kemp Eagle using the same prop. I then tried an APC 9x4, which is a somewhat faster prop than the Taipan, and the M.E.C got this up to 6,900 rpm against the 6,700 rpm of the Mills and the 6,300 rpm of the Kemp. There's no way of knowing the specification of the 9 inch prop that the engine was claimed by the makers to turn at 7,000 rpm, but on the basis of this test the claim seems entirely credible.

I then tried the 8x6 Taipan prop, which the M.E.C swung at 6,400 rpm, again faster than the Mills at 6,200 rpm and the Kemp at 5,700 rpm. On the basis of these figures, it's obvious that using the recommended airscrews the MEC was the clear winner in this particular contest! The implied power output of the MEC on the basis of this admittedly incomplete test appears to be of the order of 0.051 BHP at around 6,700 rpm. Nothing to get that excited about, but pretty good going in 1948 for an engine weighing less than 2 ounces! The unknown designer had reason to feel pretty pleased with himself!

But not for long. In the same month that the MEC was launched upon the market, Mills came out with their magnesium-case Mk II Series I version of the 1.3. This was a significantly lighter and more powerful engine than its Mk I predecessor, and would have put the MEC firmly in its place performance-wise. And then there was the ubiquitous 1 cc E.D. Bee, which undersold the lot of them at �2 5s 0d at the time. Just for fun, I tried a well-used Mk I Series I Bee on the same props, and it got the 9x4 Taipan up to a smooth and effortless 7,400 rpm without breaking a sweat! The other props were turned at similarly faster speeds. It's really hard to see how the MEC could compete with these second-generation designs which looked to the future rather than to the past.

This in no way detracts from the fact that the MEC on test proved to be a really delightful little engine to handle, and there's no denying that when it came to power-to-weight ratio it could give any of its competitors a run for their money! In making that claim, the promoters of the engine were being completely truthful.

Aftermath—the Lionheart 2.5 cc faux twin

We saw earlier that the MEC continued to be offered for sale by Premier Aeromodel Supplies up to July 1949. At some earlier point in 1949, the Premier company had introduced a second model engine. This was the 2.5 cc Lionheart "dummy twin" sideport model, which was made available in both diesel and glow variants. It's unclear whether or not the same manufacturer was involved, but it's certainly possible or even likely.

This unusual engine looked for all the world like an opposed-twin design, but it was in reality a single-cylinder unit—the second opposed "cylinder" was a dummy which actually served as the fuel tank. The manufacturers were at some pains to point this out in their advertising—presumably the engine's appearance caused some confusion!

The intended use of the Lionheart was expressly to power scale models, then still very much in vogue. The recommended airscrew was a 10x6—there was no specific recommendation for control line or free flight use, although the advertising did claim that the engine incorporated a "perfect set-up for Control Line running". Claimed speed with the 10x6 prop was 5,500 rpm and the engine was said to be good for maximum speeds in the 6,000-7,000 rpm range. The engine could be either beam or radially mounted.

The Lionheart sold for the not-unreasonable price of �4 10s 0d. Like its conventional 1.2 cc predecessor, it appears to have sold in very small numbers, and consequently examples are in extremely short supply today. We did not have access to an example during the preparation of this article, and the attached images were extracted from Clanford's book.

According both to the manufacturers and to the tables in Ron Warring's previously-referenced book, the Lionheart had a bore and stroke of 0.580 in. (14.73 mm) and 0.595 in. (15.11 mm) respectively, giving a bore/stroke ratio very similar to that of the MEC These figures give a calculated displacement of 2.57 cc (0.157 cuin) which is at odds with the figure of 2.48 cc (0.15 cu. in) quoted both by the manufacturers and by Warring. In the absence of an actual example to check, the basis for the discrepancy cannot be established.

As far as we are able to determine, the Lionheart represented the swan-song of Premier Aeromodel Supplies in the model engine business. In fact, the company itself was apparently experiencing difficulties as of late 1949, and evidently ceased trading at some point in 1950, at least under the former name. The Hornsey Rise address likewise disappeared from the model scene and subsequently from the London address book when the area was re-developed. Perhaps the competition from nearby Ripmax was too much to overcome.

Conclusion

Many parallels can be drawn between the MEC 1.2 cc diesel and the contemporary Milford Mite of generally similar displacement. Both engines were of an "intermediate" displacement and were made in relatively small numbers by (or for) a small local business as opposed to a major manufacturer. Both were sold primarily through a single sales outlet at a specific location, and coincidentally their respective sales locations were only a matter of some 10 miles apart. Both engines were advertised in the contemporary modelling media, but other factors prevented them from achieving any real prominence.

The MEC was a significantly better-made engine than the Mite, but the fact that it never seems to have overcome its dependence upon the restricted geographic sales area covered by the Model & Air Sports consortium confined it to the sidelines and eventually doomed it in commercial terms. A further factor was doubtless the retrograde nature of the engine's design, which undeniably looked very much to the past rather than to the future. Basically, the MEC was out of date as soon as it was released.

All of which is a pity, because this is a really nice little engine which deserves to be better remembered than it has been hitherto. We hope that this article will help to redress the balance in that regard!

This page designed to look best when using anything but IE!

Please submit all questions and comments to

[email protected]

|

Unless otherwise expressed, all original text, drawings, and photographs created by

Ronald A Chernich appearing on the Model Engine News web site are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 License. |

|