Deezil vs. AHC

The Diesel War that Never Was

by Adrian Duncan

August 2011

Revised:

September 2013

Two distinct but related model diesel designs originated in New York City in the latter half of the 1940's. These are the Deezil and AHC diesel, both of a nominal 2 cc displacement. Neither design ever came close to realizing its potential, but this was for entirely distinct reasons, as we shall see.

Because it never actually achieved full production status, the AHC diesel has been largely forgotten by all but our own Motor Boys. We are greatly indebted to these gentlemen for going well beyond the mere call of duty to preserve a tangible record of this very elusive engine. We will take full advantage of their efforts in the following article.

By contrast, the Deezil not only reached the market but did so in spectacular numbers. There has been a considerable amount of open discussion relating to this engine on a number of widely-read modelling forums over the past few years. These discussions confirm that while the Deezil enjoys the dubious distinction of being generally regarded as probably the worst commercial model diesel ever offered to the public, it nonetheless continues to fascinate today's model engine aficionados. It's unclear whether this fascination arises from the engine's unique place in the history of American diesels or from simple curiosity as to the extent to which it merited its truly dismal reputation—could it really have been that bad? Perhaps it's simply a case of hope springing eternal.

Whatever the motivation, some valuable information regarding the history and development of the Deezil has emerged from these on-line discussions. This has included some invaluable recollections from a number of individuals who were "there" at the time. Capturing this information as it was made available seemed to me to be a very worthwhile exercise, so I began to compile a record of such comments to serve as references during the preparation of this article. Our sincere thanks are due to all of those individuals who have shared their recollections and insights in this way.

Fair enough, but why couple the Deezil story to that of the AHC? Well, although the Deezil and AHC model diesels were developed by two separate and competing companies, their genesis was very closely related—in this case quite literally! Indeed, the announcement of one may well have stimulated the release of the other. This being the case, it seems entirely appropriate to set down the story of the two models in a single narrative which summarizes the full scope of information elicited to date and puts it in context. If you agree, please read on...

In The Beginning

The first of our two competing companies was founded in 1931 as America's Hobby Center (AHC). This company was established as a distribution and retail outlet for model goods of all kinds. It traded from premises located at 146 West 22nd Street in New York City, where it was to remain for the next 70 years apart from a brief move to an address on Lexington Avenue in the late 1940's.

1931 was a challenging year for the establishment of a new business based upon the selling of "luxury" items such as modelling materials. The Great Depression was in full swing at the time and an unemployment level of well over 20% meant that discretionary spending in the USA was highly constrained. Nevertheless, the new business weathered the storm and became very successful, eventually blossoming into one of North America's largest retail and world-wide mail order modelling businesses. Few aeromodellers who were active during the Golden Years of the hobby did not deal with AHC at one point or another—I myself was a regular mail-order customer from outside the USA.

AHC was established as a joint proprietorship by the four Winston brothers, each of whom had a share in the business. This arrangement was still in effect when America was drop-kicked into WW2 by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour in December 1941.

Two of the Winston brothers became directly involved in the ensuing conflict, enlisting in the US armed forces and going off to "do their bit". However, the other two (Bernie and Harry) did not become directly involved, instead remaining behind in New York to keep the AHC business going. Presumably to simplify matters in the event of one or both of the military Winstons becoming a casualty of war, the shares of the two departing brothers were evidently bought out by the two who stayed at home.

Both of the military Winstons survived the war and returned to New York, presumably hoping to resume their involvement with AHC, which was still very much a going concern. However, this is where things began to get a bit rocky—the stay-at-homes refused to let them back in! It's not known whether or not there had been any prior understanding, formal or otherwise, that the military brothers would be re-admitted upon their return, but if such an agreement did exist it was not honoured.

We have no first-hand information regarding the effect which this situation had upon relations between the Winston brothers. It would however be entirely understandable if some fairly strong feelings developed between the two pairs of brothers—here were the two who had voluntarily given up their shares in the successful business which they had spent ten years helping to develop being denied re-entry to that same business after serving their country for nearly four hard and bitter years of fighting at great personal risk. Many a family feud has started with far less provocation!

Whatever the emotions involved, the outcome of this chain of events was an immediate move by the rejected brothers to establish their own model supply business in direct competition with their AHC siblings. Thus was born the second of our two competing companies, Gotham Hobby Co, which traded from premises at 107 E. 126th Street in New York City. It's extremely difficult to resist the conclusion that a desire to beat their brothers at their own game may have played a role in this matter.

Some readers may wonder where the name "Gotham" came from. Contrary to popular belief, it's nothing to do with Batman, who first appeared in 1939 as a resident of a fictitious metropolis called Gotham City which undeniably bore a strong resemblance to New York. In reality, the term originated way back in 1809, when the name Gotham appeared as a reference to New York City ("Gay Gotham") in a book by Washington Irving (1783-1859), best known as the author of "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" and "Rip Van Winkle". The book in question was a satirical history of the 17th century Dutch regime in New York ambitiously entitled "A History of New York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty", ostensibly written by the imaginary author "Dietrich Knickerbocker", a supposed eccentric Dutch-American scholar. The story goes that Irving took the name "Gotham" from New York's insane asylum of that name, applying it to New York in recognition of the even then somewhat unconventional approach to life of its inhabitants.

The book quickly became assimilated into New York folklore, to the point that any New Yorker who could trace his ancestry back to the original Dutch settlers was termed a Knickerbocker. Moreover, the name "Gotham" somehow stuck as a colloquial nickname for New York City. The term was clearly familiar to the military Winstons, who applied it to their new business located in that city. It was also clearly well-known to Bob Kane and Bill Finger, the creators of Batman, who had used it in 1939 as the hometown of their famed superhero.

Having set the scene by tracing the origins of our two competing companies, let's now look at their respective activities in the model engine field.

The AHC Model Engine Lines

AHC was an early entrant into the model engine field, choosing from the outset to compete strictly on the basis of ultra-low prices, with factors such as performance and quality taking a seat in the very back row. The prevailing philosophy appears to have been that if you price an engine low enough, you'll make money because people will buy it by the truckload regardless of any shortcomings. Moreover, if the thing fails to give satisfaction, it will be consigned to the rubbish bin with little concern or recrimination against the makers simply because of the minimal investment which it represents.

The main driving force behind the AHC operation appears to have been Bernie Winston. Recently a post appeared on a widely-read modelling forum from an individual who worked at AHC during the late 1940's and early 1950's. He remembered Bernie Winston as a likeable chap who was always very pleasant to interact with but at the same time was not averse to making a buck by whatever legal means lay to hand, including the marketing of basically "junk" engines! He did credit Bernie Winston with being among the pioneers of discount mail-order marketing based on high-volume selling and this is undoubtedly a fair assessment.

Another individual posting on a different thread recalled Bernie Winston as being a genuine enthusiast with a sincere interest in the ongoing development of model aviation. Reportedly he bought every book on the subject that he could lay hands upon and took great pleasure in discussing the topic with all and sundry. This individual also recalled that Bernie was a great guy to get along with, although he admitted that AHC's business strategies perhaps reflected another side of Bernie's character.

AHC began its direct involvement with the model engine market in 1936, when the company took control of the development and marketing of the well-designed and competently-executed Loutrel .517 cuin spark ignition motor. This was one of the earliest commercial model engines of them all, having been introduced in 1931 by Louis Loutrel of Brooklyn, New York, and produced to good standards in small numbers from that time onwards. Succumbing to the lure of mass sales driven by low prices, AHC quickly engineered the decline of the Loutrel into the infamous G.H.Q., accepting steadily eroding quality in the process as the inevitable cost of said low prices. Very few people ever got a standard G.H.Q. to run.

The machining work involved in the manufacture of the G.H.Q. was reportedly carried out at a machine shop run by Harry Winston. Several posters on the various modelling forums have claimed (rightly or wrongly) that Harry Winston's machine shop was one of the few in the USA that didn't get a Government production contract following America's entry into WW2 in December 1941. Some unkind souls have speculated that the Government inspectors took one look at the G.H.Q. and figured that America's war machine deserved something a little better! This may possibly explain why the G.H.Q remained available throughout WW2 and beyond.

Following the conclusion of hostilities, AHC wasted no time in expanding their participation in the model engine market with a series of engines which upheld the established G.H.Q tradition by combining amazingly low prices with a breathtaking absence of quality! In fact, they were so marginally useable that they and others like them have acquired the name of "slag engines" among today's collectors. The chief defining feature of these masterpieces of mediocrity was the absence of a cylinder liner—the untreated aluminium piston ran directly in an untreated aluminium bore. Some of them ran, but many didn't and the majority of those that did were marginal performers. Even the best of them didn't last long in service, often being completely clapped out after only a few runs. It was a simple case of pour in the oil and hope for the best!

In fairness to AHC, it has to be admitted that they did not invent the slag engine concept. This unique approach to model engine construction actually had its roots in pre-war Detroit, where the Synchro B-30 slag engine first appeared in 1940. This was soon joined by the 1941 Rogers and Pioneer Brown slag engines from Philadelphia. However, after the war AHC quickly recognized the commercial potential of this highly questionable technology, becoming one of its most prolific exponents.

AHC entered the slag engine fray in 1946 with the first of their series of Thor "B" .292 cuin engines, which appeared in three successive variants during 1946, culminating in the supposedly improved Super Thor "B" later in the year. In 1947 there was the Genie .29 which was ostensibly made by Genie Models in New York but was basically just a Thor "B" with the cylinder fins turned around and the Thor name ground off. Motor Boy Bert Streigler, whose Deezil replica we'll see later, says that they were called "Thor" because that's how your fingers felt after trying to start one!

The illustrated example of the Super Thor "B" is one of the better ones. It has been run (proving that some of them did run!) and still has excellent compression, but I wouldn't bet on it lasting long in service! That said, the Society of Antique Modellers (SAM) has run a number of contests exclusively for models powered by slag engines, with good entries and many successful flights. So not all of these engines were completely useless.

In 1948, AHC introduced a new range of slag engines under the Buzz label. These appeared in four displacement categories—the Buzz "A" of .199 cuin displacement, the Buzz "B" of .292 cu. in., the .342 cuin Buzz "C" and finally the Buzz "D" which packed all of .610 cuin. All four models appeared once again in 1949, albeit in glow-plug form with no provision for a timer.

There was also the Buzz CO2 unit, a tiny 0.0052 cuin engine which ran on compressed carbon dioxide. This was made for AHC by Campus Industries and was essentially identical to the manufacturer's own Campus "Bee" model.

The most intriguing model offered by AHC was a .045 cuin glow-plug motor known as the "Glo-Wee". This was advertised in 1949 along with the Buzz glow-plug models, but no examples are known to exist today. It appears highly likely that production never got off the ground.

The AHC Diesel

Following the conclusion of WW2, American servicemen returning from the European theatre brought back examples of a new type of model engine which had been developed in Europe during the war years. These engines ran without any ignition support system, a concept which must have really startled a lot of folks! Thus the model diesel reached American shores for the first time.

As of late 1945 when these engines first appeared in America, the commercial glow-plug was still over 2 years in the future. Accordingly, the diesel offered the sole alternative then available to spark ignition. The great advantage of the diesel principle was the fact that its use eliminated the heavy, parasitic and often unreliable ignition system required by the spark ignition types. A number of American manufacturers quickly recognized the commercial potential of such a power-plant.

By late 1946 several American manufacturers had begun to market diesel models, with more soon to follow. A number of these early American designs possessed considerable merit by any standard—the C.I.E., Vivell and Drone models come immediately to mind. It's actually very much to be regretted that most American manufacturers ended their association with diesels so quickly after the advent of the glow plug—some of them certainly got off to a very impressive start.

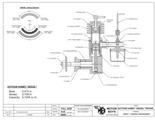

Given Bernie Winston's previously-noted interest in developments connected with model aircraft, AHC must have become aware of diesels as quickly as any of their competitors. It appears likely that they commenced the development of a 0.12 cu. in (2.cc) diesel model at some point in 1946. The resulting design was a completely conventional long-stroke side-port compression ignition engine of its period. Its unique features were the complex die-cast crankcase with twin teardrop exhaust stacks, a long and rather delicate integrally-cast venturi, somewhat fragile beam mounting lugs with open-ended mounting holes and a backplate that was designed to be stamped from 1/16" aluminium sheet.

According to the AHC entry in Tim Dannel's indispensable American Model Engine Encyclopedia, the AHC diesel was scheduled for release in production form during 1947. The impending arrival of the engine was duly announced, but for reasons which remain somewhat conjectural it never actually put in an appearance on the market.

So far, it's all familiar—there were a lot of still-born model engines which were designed and announced but subsequently disappeared without trace. In the case of the AHC, matters went somewhat further than this. It seems that the project actually reached the early stage of production with the creation of the required die and the manufacture of almost 1000 crankcase castings. Moreover, AHC appear to have completed several engines, presumably to serve as prototypes for testing purposes.

The sole surviving image of an original AHC diesel prototype shows that this example differed in certain details from the replicas produced years later by Ron Chernich and others. It seems to have used a tank and surface jet needle valve set-up that was borrowed directly from the contemporary Genie 29 slag engine. No attempt was made by Ron to replicate the Genie tank setup, hence his replicas have no tanks. They do however use original Genie needles!

That was as far as the project went in AHC's hands—the project was permanently shelved despite a considerable investment having already been made. There must surely have been some compelling reasons for the abandonment of this investment. It's entirely possible that the test results in prototype form showed the engine to be basically uncompetitive in performance terms—later test results certainly support this possibility, as we shall see. However, a number of other factors may well have been involved, as ably documented by the late Roger Schroeder in his article "What Happened to the AHC Diesel?" which appeared in Volume 26, No 4, Issue 148 of the Engine Collectors' Journal, published by The Model Museum, ISBN 1066-7172, October 2001, p8.

Roger's broad conclusion was that the engine had embodied a collection of poor design choices, the recognition of one of which simply highlighted the next in domino fashion. For starters, the cases were cast from the genuine "pot metal", a material of deservedly evil reputation which is both weak and notoriously difficult to machine and thread properly. It's not unlikely that machining difficulties presented themselves during the prototype production phase, quite possibly resulting in the spoiling of some castings.

Over and above the material issue, there's ample evidence that a substantial proportion of the original AHC crankcase castings were seriously flawed even before any attempt was made to cut metal. Many appear to have been removed from the die at such a high temperature that the integrally-cast intake tube warped badly out of line when it cooled. The crankcase in the attached illustration displays this problem. There were also a fair number of cases on which the metal did not flow fully into the cavity which formed the right-hand exhaust stack, leaving that feature incomplete. It's actually possible that there were depths of crudity below which even AHC were not prepared to descend!

Even if the castings had all been useable, the crankcase design itself left much to be desired in several areas. Firstly, the front face of the crankcase was set too far back to allow the location of the crankweb in such a position as to align the con-rod centrally on the bore axis viewed from the side. Consequently, the con-rod column was forced to run to the rear of its ideal central location along the bore axis, thus imposing a fore-and-aft rocking couple upon the piston. It would have taken a relatively minor amendment to the pattern to deal with this issue, but as-cast it can't be done. The designer clearly recognized this problem (if indeed he did recognize it!) only after the investment in the 1000 cases had already been made. So they were stuck with a rod that was constrained to run off its ideal axis.

A further issue affecting the rod was the fact that the case as cast did not provide sufficient clearance to accommodate the side-swing of the rod around mid stroke. Ron Chernich found it necessary to use a Dremel tool to create a pair of channels at the sides of the case to provide the necessary swing clearance. The need for the manufacturers to carry out this step would have added substantially to manufacturing costs. Even after this was done, the rod was limited to a very minimal column thickness by diesel standards. Years ago, the late George Aldrich showed that the stiffer the rod, the better the performance. The AHC came nowhere near addressing this criterion. Accordingly, they were stuck with an underfed rod that was constrained to run off its ideal central alignment. The issues were mounting ...

Assembly was another matter that was not accommodated by the design. The arrangement of the upper crankcase casting is such that the piston and rod have to be installed as an assembly—you can't fit the piston following rod installation. However, the available space severely limits the rearward movement of the assembly for installation, so you have to tilt the rod to slip the big end over the crankpin. This makes installation with a closely-fitted big end bearing of adequate length impossible. The fix was to use a skinny rod with very short bearings—likely a stamped item in the original design. So now we have a skinny rod with too-short bearings that is constrained to run off-line! Worse and worse ...

Of course, this in turn led to a further problem—the short bearings at both ends meant that only a very minimal amount of wear was required to free the rod to "wobble" out of its correct vertical alignment (viewed from the side). Hence the rod now had a tendency to wander off the vertical in a fore-and-aft direction, creating both excess friction and rapid uneven wear. I actually elected to replace the rod in my example with a more substantial item after only a few hours running time. I hasten to add that this is a Bernie Winston design problem, not a reflection of Ron Chernich's outstanding workmanship! The new rod is significantly stiffer and has far longer bearings. It has so far proved extremely reliable. However, fitting it was a challenge ...

The use of a thin stamped aluminium backplate was also a poor design decision since it left a very sizeable gap between the inner front face of the backplate and the rear of the crankpin as well as creating a substantial annular space around the inwardly-protruding boss of the stamped backplate. This in turn created a lot of unnecessary dead space in the crankcase, thus impairing the engine's pumping efficiency by reducing its base compression ratio. It also left the con-rod big end free to work its way off the crankpin if it felt like doing so.

Finally, why they chose to employ an integrally-cast 0.125" I/D. intake tube is quite beyond me—even the 0.140 bore adopted by Ron in his replicas is totally inadequate for an engine of this displacement. However, it's about all that the casting will accommodate given the fragility of this feature. Once again, there was an easy fix available—either use a larger O/D tube or (preferably) incorporate a cast boss on the rear of the crankcase into which a separate venturi could be threaded. Quite apart from the strength issue, the latter approach would have allowed the use of a venturi of adequate throat area which could easily be replaced in the event of a failure. It would also have had the great benefit of allowing the installation of the gudgeon pin to take place through the induction port after installation of the rod, thus dealing with the rod installation problem mentioned earlier. However, it seems that once again this only became apparent (if indeed it did become apparent!) after the investment in the castings had already been made.

Overall, one gets the impression that Bernie Winston (or whoever designed this engine) didn't fully understand either the mechanical or functional principles that govern the operation of a model two-stroke engine. Consequently, the design incorporated a number of barriers to optimum performance and longevity as well as presenting some significant manufacturing challenges. Looked at from this perspective, the abandonment of the project becomes easily understandable.

Regardless of the reason(s), the decision not to proceed to series production would normally have been the end of the matter, with no more being heard of the AHC diesel. However, in this instance the work completed up to the abandonment of the project was not lost. The cases were preserved together with a certain amount of design data. These materials passed through a number of hands during the ensuing years, including those of Motor Boy Tim Dannels, editor of the Engine Collector's Journal.

Our intrepid Editor Ron Chernich was among those fortunate enough to acquire a stash of cases from Tim along with what remained of the design details. This was a happy occurrence since Ron was sufficiently skilled and dedicated to generate a set of CAD drawings and complete a short production run of this mega-rare engine using original AHC cases and needle valve components. The bore and stroke of Ron's replicas are 0.468" (11.89 mm) and 0.680" (17.27 mm) respectively for a displacement of 1.92 cc (0.117 cuin). The replica engine weighs 129 gm (4.55 ounces) without tank.

It is entirely thanks to the efforts of Ron and others like him that a fortunate few of us are able to enjoy the unusual experience of handling a classic model engine that never actually appeared on the market in its day! My own example of Ron's replica AHC is a lovely bit of work altogether, reflecting great credit upon Ron's skills. It bears the number 8, indicating its position in the very short series produced by Ron. It does however have one major flaw as a true replica—the record clearly demonstrates that AHC would never have allowed a model engine of this quality to bear their name! Ron describes the production of these engines in detail in the AHC Project pages on this website, as well as that of several experimental models using both RV and FRV induction. Accordingly, there is no need to repeat any of that material here.

Our possession of this fine replica places us in the happy position of being able to test the engine to reach an assessment of how the AHC diesel might have fared in the model engine market of 1947 if it had actually made it into production. But before we do so, we must turn our attention to the "other" diesel model from the Winston family—the infamous "Deezil" with which Gotham Hobby challenged the market. This one definitely did make it into production, so it deserves our full attention.

The Gotham Hobby "Deezil"

We saw earlier that following the failure of their efforts to become re-involved with AHC, the two rejected Winston brothers wasted little time in establishing their own hobby supply firm under the Gotham Hobby name. It's very difficult to resist the conclusion that one of their goals in taking this step may well have been to make themselves a thorn in the sides of the two brothers who had rejected them.

By late 1946 American-made model diesel engines had begun to appear on the domestic market. Gotham Hobby clearly became aware of this and soon decided to jump onto what might become a bandwagon of sorts by introducing a diesel of their own. It's entirely possible that the preliminary announcement of the AHC diesel in 1947 may have fuelled their ambitions by giving them a target at which to take aim. As matters turned out, the AHC diesel did not actually materialize in production form, but this did not stop Gotham Hobby.

The earliest advertisement for the Deezil which I have found so far was placed by Gotham Hobby in the April 1948 issue of Model Airplane News (MAN). The engine was referred to in this advertisement as the Deezil "A", although the "A" seems to have been dropped fairly quickly. The quoted price of the engine at this introductory stage was $12.95—a not unreasonable figure for an engine of this very basic specification if it was constructed to appropriate standards. The advertisement claimed that Gotham Hobby had put "a solid year of design and development into this engine", a statement which is somewhat open to question, especially given the end result! If true, it implied that development of the design must have commenced in early 1947. As we shall see, there is a strong possibility that in reality Gotham Hobby repeated AHC's earlier strategy with the Loutrel by simply taking over an existing design by others.

The Deezil was a completely conventional long-stroke sideport diesel of its day, being based upon a die-cast crankcase with bronze (later brass) bushed main bearing and having bore and stroke measurements of 12.01 mm (0.473 in.) and 17.98 mm (0.708 in.) respectively for a displacement of 2.04 cc (0.124 cu. in.). The engine weighed 148 gm (5.22 ounces) without tank—a little more than the rival AHC model. It was also somewhat more bulky than its counterpart.

The design of the Deezil avoided a number of the pitfalls which were incorporated in the AHC model described earlier. For one thing, the crankcase was cast out of proper casting alloy as opposed to pot metal, thus avoiding the machining difficulties of the latter material. For another, the design was such that the rod installation issue noted with the AHC was not a factor in the Deezil—the piston could easily be fitted following rod installation. Moreover, ample rod swing clearance was provided to allow the use of a rod of adequate proportions. In addition, the engine was quite generously ported for an engine of this specification, the induction port in particular being notably large. All cylinder ports were rectangular in shape, being produced by milling. Cylinder, piston and contra piston were all made of steel. The aluminium alloy cooling jacket was quite substantial, being of the screw-on variety. This type of assembly is very effective in promoting good heat transfer between the cylinder and the cooling jacket.

On the downside, the Deezil undeniably presented a few undesirable features. One rather obscure anomaly was the form of the mounting lugs. The casting was clearly pushed out of the die to the rear, the draft angles being set accordingly. This resulted in the beam mounting lugs being significantly thinner at the front (viewed from the side) than at the rear. As a result, the engine's thrust line was noticeably out of alignment with the plane of the mounting surfaces. This of course is merely an "oddity" that has to be accommodated during mounting rather than a real fault with the design.

Of greater concern was a feature which the Deezil shared with its AHC counterpart, namely the very minimal length of the con-rod small-end bearing. In addition, the rod itself was made of brass, not perhaps the ideal material for this component in terms of durability and weight. Coupled with the brass gudgeon pin seen on most examples (but see below), this was a less-than-optimal combination in engineering terms.

Another less than praiseworthy design feature was the means of prop mounting. Both the prop driver and prop washer were identical, being stamped out of 1/16" steel sheet. The central opening was D-shaped, corresponding to a flat milled in the front portion of the shaft. The driver and washer were thus both keyed to the shaft—a good feature given the fact that the driving faces of both components were completely smooth. The problem was that the thin driver and washer tended to cut into the unhardened material of the shaft, rapidly inducing a substantial "wobble" in any engine that could be persuaded to run. The one positive feature was the fact that the smooth driving faces allowed for some prop slippage in the event of a crash, thus presumably protecting the shaft to some extent.

However, the piece de resistance in most Deezils was the crankshaft. The vast majority of these engines featured a composite item consisting of three separate elements—main journal, crankweb and crankpin. These were simply brazed together, presumably in a jig. The fact that the crankweb was stamped from a thin piece of sheet steel did nothing to inspire confidence in this truly Mickey-mouse assembly. The working life of this component could probably be measured in seconds!

The induction tube screwed into a threaded opening in a substantial boss formed at the rear of the case, no lock nut being employed. The bore of this tube was parallel throughout, having an internal diameter of 0.218" (5.56 mm), significantly greater than the 0.125" I/D of the original AHC. Early models may have been supplied with tanks, although the vast majority seem to have been sold without this accessory.

The spraybar was threaded for almost its entire length, having only a short plain section at the fuel pickup end. The holes through which it traversed the intake tube were threaded to match, the spraybar being held in the correct alignment for the single jet hole through the use of a locknut. A standard split thimble provided the necessary needle tension.

The original engines as illustrated in the April 1948 MAN advertisement featured a composite compression screw which consisted of a stiff wire control arm pressed into a hole drilled transversely through the head of a standard slot-head 3/16-24 machine screw. Interestingly, they were also provided with a 1/16" blind hole in the top of the cylinder jacket for the installation of a stop pin, although this fitting is missing from the illustrated NIB example as well as the one depicted in the advertisements. Presumably it was an owner option, to be installed only after the required range of compression settings had been established by testing. Later versions used a one-piece comp screw which was simply a bent piece of steel rod threaded 3/16-24 at the cylinder end. They also lacked the hole for the stop pin—after all, you only need such a fitting if the engine's actually going to run! We mention these details because the composite comp screw and stop pin hole seem to be indicators of an early engine, a matter which has some potential significance, as we shall soon see.

Another feature which evolved over the course of time was the outside diameter of the cooling fins. What appears to be the earliest model in my possession has a cooling jacket with an O/D of 1.175" A second and evidently later example sports a jacket having a 1.125" O/D, while the other two examples presently in my collection have jackets of only 1.055" diameter.

An interesting detail which seems worth mentioning is the fact that the illustration of the engine in the advertisements shows it fitted with a length of fuel tubing. This is too short to be used to connect the engine to a separate tank. Moreover, no tank is depicted as having been supplied with the engine, at least in this image. Despite this, it appears certain that the engines were indeed supplied with this length of tubing—it is included in the parts list which accompanied new engines. Moreover, both of my own NIB examples came equipped with lengths of tubing which appeared to be original.

There have been persistent rumors that some of the early Deezils were actually supplied with tanks - the possibility is noted in the Deezil entry on page 64 of Tim Dannel�s �American Model Engine Encyclopedia�. At the time when this article first appeared, I had no evidence to support this possibility, but in 2013 I acquired an as-new boxed example of a Gotham Deezil which was fitted with what appeared to be an original tank. It thus appears that some of the engines were indeed supplied in this form.

The Deezil was extensively advertised in MAN and non-aeromodelling magazines such as Popular Mechanics and Popular Science from early 1948 onwards. Either sales at the original asking price of $12.95 were discouraging or the promoters weren't making enough money on the engines to suit them and decided to go after bulk sales, pricing the engines accordingly. Regardless of the reason, the price quickly fell to $5.95 for a fully assembled engine including accessories. No doubt quality also fell accordingly as costs were slashed. As time went on, the engine was offered at ever decreasing prices and in various forms, including a fully machined, ready to assemble kit. By its final year of sale in 1955, the price was down to $1.95! Presumably by that time they were selling off existing new old stock.

Unlike most other manufacturers, Gotham Hobby did not package these engines in custom-made labeled boxes. Instead, they used generic corrugated cardboard fold-up mailing boxes supplied by Corrugated Paper Products Inc. of Brooklyn, New York. A Gotham Hobby Co. mailing label bearing the name and address of the customer to whom the engine was sent was stuck onto the top of the box together with the required postage. The stamp on one of my Gotham boxes has a value of 7c for postage from New York to an address in Detroit—a sign of changed times if ever there was one!

An instruction sheet was included with each engine. Two styles of sheet are known to me at present. The first (and least commonly encountered) has a set of operating instructions on one side and an exploded view of the engine with a parts list on the other. There are no assembly instructions on this leaflet, implying that it predates the period during which the engines were offered in kit form. It does however show the bent rod style of comp screw and the brazed-up crankshaft, implying that there may have been a still earlier version of which I am presently unaware. The boxed engine with which this sheet arrived is consistent with the drawing.

A clue to the maker's recognition of the engine's quality issues may be found in the recommended fuel formula—60% SAE 70 or 60 motor oil and 40% ether! Shades of the slag engines, for which a 50/50 gas-oil mix was specified. Presumably the theory was that if one poured enough thick oil into the engine, one might get enough compression to achieve a start!

When the engines began to be offered in kit form in 1950 or thereabouts, a revised instruction sheet came into use. This version appears to be far more common today than the earlier edition. One side of the revised sheet was entirely devoted to extolling the virtues of this masterpiece of mechanical precision! The other side of the sheet included assembly instructions for the kit, together with operating procedures. The exploded view of the engine no longer appeared—strange, because it might have really helped those building the engine from a kit. Oddly, the recommended fuel formula had been changed—the leaflet now specified equal parts of castor oil and ether.

In his invaluable American Model Engine Encyclopedia, Tim Dannels reports the existence of a single example of a ball-bearing Deezil. Wot? A ball-race Deezil? It's true, folks—such a variant was briefly advertised in 1948 along with the standard plain bearing model, although it was not illustrated in the advertisement and was clearly sold in very small numbers, if at all.

The sole presently-known example of such an engine has the shaft housing shortened by 1/4 in., with a steel sleeve pressed over the front of the shortened bearing housing. This sleeve contains a ball bearing, the shaft being shimmed to fit. The engine thus features a single ball bearing at the front of the shaft rather than the more usual rearward location, implying that the idea was possibly directed at improving the engine's performance in model car service, where such a bearing might have value given the lateral loadings imposed at that point by gearing or flywheel mass. This example also has a brass restrictor sleeve fitted to the intake, presumably to improve suction.

It is not known for sure whether or not this is the true ball-bearing Deezil or a standard Deezil which has been modified by an ingenious owner. All that can be said is that this single example was found in a Gotham Hobby box, which of course does not preclude the possibility that it represents an owner modification of a standard model. The finding of further examples would do much to help to clarify this point.

Many things have been said about the Deezil over the years, almost all of them bad. In a nutshell, the Gotham Hobby management appears to have followed the same road as their siblings over at AHC by sacrificing quality for low price and presumably hoping that their customers wouldn't notice! Examples of appallingly poor standards of manufacture immediately present themselves when one examines a typical Deezil. Features such as the flimsy three-piece crankshaft held together by brazing at the joints; the crankweb stamped from soft steel plate; the brass con-rod, main bearing bushing and gudgeon pin; the absence of any vestiges of compression; the usually-loose contra-piston and the brazed-in-place cylinder hold-down flange with its potential for misalignment scarcely recommend themselves to any potential buyer. A few examples have turned up in which the shaft components are simply pressed together without any brazing at all!

One issue that was clarified in a recent modelling forum thread was the alignment of the brazed-on cylinder flange. It turns out that there's a very minimal shoulder on the cylinder outer wall at the level of the upper face of the cylinder mounting flange. The individual posting the comment had measured several examples of the Deezil and had found that the nominal O/D of the upper (threaded) portion of the cylinder was 15 mm while the lower half below the flange was 14 mm. My own subsequent measurements confirm this feature, which I had not previously noticed. This explains how the manufacturers were able to position the mounting flange for brazing with a relatively low chance of it being misaligned.

Motor Boy Les Stone was one of those who took the plunge with the Gotham Deezil, as recalled in this account:

"I fell victim to the Gotham Hoax many years ago. I was watching the magazines until the price finally fell to $2.95 for one engine. (The ads confirm that this had happened by September 1950—A.D.), I jumped on that one and when it arrived, proceeded to try starting it for a couple of days until my arm felt like it was about to drop off!"

The fact that there was no Internet at the time presumably did much to slow the rate at which the word got around. In addition, Gotham Hobby soon began to focus their advertising on non-aeromodelling publications such as Popular Science and Popular Mechanics. These ads of course reached prospective buyers who were not necessarily connected with the aeromodelling world. As a result of these factors, the engines' shortcomings did not prevent them from reaching the market in large numbers over a considerable period of time. They seem to have found many buyers, most of whom were doubtless as disappointed as Les but lacked the technology to spread the word. You'd never get away with this kind of thing today.

Given the above comments, it's noteworthy that the promoters specifically stated on the later version of the instruction sheet that the engine could be returned within ten days of receipt if the customer wasn't satisfied. One might imagine that the engines would have been returned by the warehouse-full under this provision! However, there were several catches. First, the return was evidently at the expense of the customer—nothing was said to the contrary. Secondly, a return didn't entitle the customer to a refund or a replacement—rather, it entitled him to receive a credit of the value of the engine less any damaged or missing parts against the purchase of any other item(s) on Gotham Hobby's list.

What this meant in real terms was that if the engine failed, the cost of any failed parts was charged to the customer regardless of whether or not the failures were the result of manufacturing deficiencies! Some guarantee! In addition, the customer had to pay the return postage. Finally, the only way that he could recover even a portion of his investment was to purchase another item from Gotham Hobby's list. When you look at it this way, Gotham Hobby couldn't lose—they kept your money regardless of how things unfolded! Small wonder if very few buyers bothered to activate this "guarantee"—it was in reality nothing of the sort! Most of the engines doubtless went straight into the rubbish bin. It's actually not impossible that any engines that were returned were simply re-packaged and sold a second time!

But were the Deezils all that bad? It turns out that there's considerable evidence to the effect that the early ones may have been quite a bit better made. This possibility was first brought to my own notice some years ago by a reported comment from no less a personage than the late and legendary George Aldrich, who was certainly a competent judge of model engines and was moreover active during the hey-day (if we may call it that!) of the Deezil. When asked directly for his recollections of the Deezil, George recalled from his own observations that some of the early examples "ran like a Mills"—quite a testimonial from one who certainly should have known. Others have reported examples of the engine which appear to be far better made than the general run.

An interesting piece of supporting evidence is actually provided by the later instruction sheet supplied with the engines. The statement is made on the sheet that the $2.95 Deezil is "...the same engine that sold for $12.95—but the demand was so great that we were able to go into mass production, and costs tumbled". This clearly implies that the Deezil started out as a limited-production engine selling for $12.95—a perfectly rational price in 1948 for a simple 2 cc diesel engine of reasonable quality. The further implication is that it was only after Gotham Hobby began to apply their unique brand of mass marketing to it that the engine was progressively trashed down to the $1.95 paperweight that it eventually became.

This lends some credibility to the often-recounted story that the Deezil was originally a higher-quality product manufactured independently from the Winston brothers and that they repeated the saga of the pre-war Loutrel/G.H.Q transformation by taking over the Deezil project, thereafter trashing it down to a price rather than continuing to offer a quality product. A frequently-repeated and perfectly believable tale is that untrained Gotham employees assembled the engines from boxes of parts without the slightest understanding of what they were doing. If it was loose enough to go together, it went together regardless of the fit! The sloppy piston and contra-piston fits in most Deezils constitute ample evidence for this—no-one who understood diesel assembly could possibly consider such fits to meet the requirements of these engines.

There's no doubt at all that examples of the Gotham Deezil have surfaced which vary widely in the quality of their construction. Several convincing pieces of evidence to this effect have surfaced on several of the modelling forums. One post documented a Deezil which featured a properly-machined one-piece steel crankshaft as well as a piston which was if anything fitted rather on the tight side, with a good "pinch" around top dead centre. The owner had not run the engine, but it was clearly well above most examples encountered today in terms of quality. Another poster reported that he had an example which featured a cylinder that was machined in one piece including the installation flange, thus dispensing with the brazing-on of the flange. It seems safe to assume that there must have been others built to these higher standards—perhaps these are the early $12.95 examples.

Until very recently, my own experience had been less fortunate—in previous years I'd had half a dozen or so examples through my hands, all of them featuring the brazed-up composite shaft, brass rod, brass gudgeon pin and woefully-inadequate piston fits. I never so much as considered trying to run one of them, since I had little doubt that even if I succeeded in achieving a start the engine would survive for a few seconds at best!

This view was completely borne out by a highly entertaining YouTube video which made an appearance in August 2010. The poster documented his very determined efforts to start an original Gotham Hobby Deezil. The example chosen for this test initially lacked sufficient compression to start. In addition, the cylinder was installed backwards. So far, a typical example! The next step was to use the better parts from three examples to make up a single engine which appeared sufficiently well-fitted to run. Using this hybrid with a fuel consisting of 70% chainsaw bar oil and 30% ether, our hero was able to achieve a start, but only through the use of an electric starter (AAARRRGGHH!). The thing ran very roughly for about thirty seconds, after which it expired with a clatter. Subsequent inspection showed that the very thin crankweb had bent on the crankpin side, thus also bending the rod! In doing so, it likely anticipated the failure of the crankpin itself by only a few seconds. Need we say more?

The Deezil Re-appraised

Taking all of the above observations together, I accepted the possibility that a few of the early Deezils might have been somewhat better-made than most of those encountered today, although I lacked any direct evidence to support this notion. I continued to hold the view that the vast majority of these engines were useless.

However, my recent purchase of the previously-illustrated early NIB example on eBay provided some significant new first-hand evidence which forced an adjustment of my views. By Deezil standards, I paid a premium price for this engine. This was a bit of a gamble on my part based entirely on the claim of the seller (with whom I'd had previous satisfactory dealings) that the engine actually had reasonable compression. Wot! A Deezil with passable compression? Could this be one of the early examples, perhaps from a maker other than Gotham Hobby? It certainly featured the relatively rare early composite compression screw mentioned previously. Anyway, I thought that it was worth the gamble.

As it turned out, I probably got very good value for my money. I dismantled the engine completely and found that it was head and shoulders above all of the other examples of my previous acquaintance in terms of quality. It retained the composite cylinder with brazed-on location flange, but the crankshaft was a sturdy and well-machined one-piece item which even incorporated a counterbalance on the web. It was in fact identical to the component reported earlier in a modelling forum post, implying that it was a standard component of the Deezil at some point in time. The crankpin and crankshaft journal were well finished, the journal being an excellent fit in the main bearing bushing. Moreover, this bushing was of bronze instead of the brass used in most examples.

The engine retained the usual brass con-rod, but the gudgeon pin was made of bronze and was press-fitted into the piston in stark contrast to the usual fully-floating brass component. The press fit is actually an important feature since the induction port at the rear of the cylinder is more than large enough to swallow the gudgeon pin, which could thus foul the port very easily unless it was secured within the piston. The bore appeared to have been properly lapped and the unrun piston and contra-piston were quite well finished. Compression was not what I'd call outstanding but appeared to be at least adequate for starting. Base compression was excellent.

The attached images of the crankshaft from this engine together with that from one of my other examples will highlight the difference in quality. The one-piece crankshaft is nicely machined and well finished, while the later brazed-up shaft appears to have a journal section which was cut from 5/16" bar stock with no attempt made to produce a finished surface! And you just have to love the thin stamped steel crankweb with its brazed-in-place crankpin!

Although I can't prove it at present, I now believe that the original Deezils used the one-piece crankshaft, bronze main bearing bushing, pressed-in bronze gudgeon pin, composite comp screw and larger-diameter cooling jacket with stop pin hole seen on my new acquisition. Based on the previously-noted forum posting, the very earliest ones may also have used a one-piece cylinder with the locating flange incorporated in unit, although I have personally yet to see any evidence for this at first hand. However, a well-fitted engine built to this specification could have been a perfectly acceptable product—quite possibly well worth the $12.95 price at which it was originally advertised.

A persuasive indication of a higher level of promoter confidence in the early examples of the Deezil is the fact that the earlier instruction sheet described in the previous section of this article included a servicing provision in place of the worthless "guarantee" presented on the later sheets. Under this provision, engines could be returned to Gotham Hobby along with a quite reasonable service charge of 75�, for which the engine would either be returned to operating condition or a new replacement supplied. This was a far more credible indication of manufacturer confidence than the so-called "guarantee" subsequently applied to the engines.

All of this is consistent with the presently-unconfirmed notion that the Deezil started out as a sincere attempt by its unknown designer to create a practical and durable engine which would serve its owners well. The designer naturally needed a marketing outlet for his product, and for better or worse his choice for that role fell upon Gotham Hobby.

In this scenario (which at present is no more than speculative), the role of Gotham Hobby was initially restricted to the marketing of the engines. However, production figures at this standard failed to meet Gotham Hobby's marketing expectations, leading them to assume control of the project with the intention of ramping up production and cutting costs by whatever means were most expedient. Naturally, they would have continued to use the better-quality components already on hand until these progressively ran out, switching thereafter to their own junked-down parts to cut costs. This would make my recent acquisition one of the early Gotham Hobby engines (which the box and leaflet prove it to be) assembled while they still had stocks of the superior components originally used, albeit without the faintest notion of how to match pistons to cylinders.

Although I was somewhat hesitant to actually run this mint NIB example, I decided that the search for knowledge more or less obligated me to give it a try. It turned out that the "good" compression was largely illusory, being predominantly created by the presence of thick oil in the engine. When diluted with a fuel prime, much of the compression went away. Despite this, using standard diesel fuel with 25% castor oil I was actually able to hand-start the engine fairly easily using an oil prime. However, after six to eight seconds of running the oil prime had run through, the viscosity of the oil in the fuel had become reduced by heat and the piston fit had become even looser as things heated up. In this state, all vestiges of compression disappeared and the engine simply died—no amount of fiddling with the compression screw would keep it going. Oh well ... at least it upheld the Gotham tradition apart from the fact that it did actually start!

Now there was no doubt at all in my mind that this engine would run fine with a slightly tighter piston fit. It might even keep going as-is on the recommended 60/40 oil/ether fuel mix—the extra oil might make the difference. All fits apart from the piston clearance were excellent. Taking all of this into account, after much soul-searching I decided to test my opinions by making a new piston for this example. Since the original piston was of steel, I elected to use the same material for the replacement component, copying the original exactly in every respect and retaining the press-fit for the gudgeon pin. I also decided to make a new con-rod for the engine—that skinny small end was just a little too minimal for my taste given that the goal was to actually run the thing!

The Deezil cylinder appears to be common-or-garden mild steel tubing which won't work-harden to any great extent, so I elected to make the piston out of a high-tensile steel that would work-harden during the initial running period (Meehanite cast iron does this too).� As far as I�can tell, the original Deezil piston was untreated mild steel, which means that the engine wouldn't have lasted too long even if it did run—it was a soft-on-soft combination. By contrast, a properly-fitted work-hardening steel piston in a soft steel cylinder should wear pretty well.

The main issue with using a steel piston is that,�unlike cast iron, steel doesn't "grow" over the first few dozen or so heat cycles, thus taking up any break-in wear. So you have to get a really fine finish on the piston surface to minimize initial wear and also need to get the piston fit pretty near perfect right from the get-go—just very slightly stiff, but not unduly so. It will then wear to a perfect fit and become work-hardened during the process.

I elected not to rebore the engine since the cylinder was virtually unused, with a perfectly fitted contra piston. The bore appeared to be quite well finished, with a taper of around half a thou over its working length. This made the fitting of the replacement piston perfectly straightforward. Some idea of the quality issue may be gauged from the fact that my new piston correctly matched to the existing bore was the better part of a full thou larger in diameter than the original.

I made the replacement con-rod out of aluminium alloy for two reasons—first, to save reciprocating weight and second, to make it very obvious that the component was indeed a replacement. I have no doubt that some future owner of this engine will try to pass it off as one of the few running original Gotham Deezils, and I wanted to leave my mark on the engine somewhere to refute this. I plan to keep the original piston and rod in the box with the engine along with a note to any future owner stating what I've done. That's about all that I can do to preserve the integrity of the record. The rule is—if it has an aluminium alloy rod and good compression, it's been nobbled! Caveat empor.

Having finished the above work, I was naturally quick to get the engine back onto the test stand. I seem to have nailed the piston fit—the engine started second flick (albeit backwards!), and ran perfectly from the outset.�Starting was dead easy throughout—a few choked flicks, and away she went. Compression remained just as good when hot, with no tendency to tighten up and sag. I put on about 20 minutes in 5-minute runs with complete cooling in between—all that I judged the neighbors would tolerate, although it ain't that loud!� It held up well—the shaft (which is of course a one-piece Gotham original) took the test in stride, so it must be made of reasonable steel.��At the conclusion of this session, the engine felt superb, with outstanding compression yet no trace of binding.

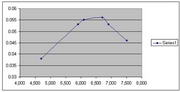

Although I kept the engine under-compressed and slightly rich due to the need to break in the piston and the rod bearings, I did do a quick leaned-out spot-check at the 20 minute mark.�The rejuvenated Deezil managed 6,700 rpm on the Taipan 10x4 GF prop that I was using�- not too bad for a 2 cc engine of this vintage and specification that is still running in.�The implied output at this speed was around 0.077 BHP.

I subsequently put a further 20 minutes on the engine, at the end of which the 10x4 prop was spinning happily at 6,900 rpm on a leaned-out spot check. Implied power output at this speed was up to some 0.084 BHP. The engine would doubtless continue to improve with some more running time, which it likely won't be getting from me.

Just for fun, I subsequently fitted this engine with the tank from the additional example mentioned earlier which I acquired in 2013. This particular example is now in the form in which I believe some of the original engines may well have been supplied. It�s certainly the best original Deezil of my present acquaintance!

This abbreviated test still leaves us wondering how a well run-in Deezil would have performed if it had been better fitted, as some of the earlier ones appear to have been. There seems to be only one way to assess this point—take a less-than-pristine original Gotham Hobby Deezil, replace all of the wonky components with properly-made and well-fitted replica items, give it a long and careful break-in and then test it!

Fortuitously enough, I had done this very thing some years ago with the least pristine example then on hand. Since that example had the infamous brazed-up shaft and brass gudgeon pin, I made a new one-piece shaft of decent steel along with an aluminium alloy con-rod complete with steel gudgeon pin. I then lapped the original cylinder (which it very much needed, unlike the NIB example reported above) and made closely-fitting replica piston and contra-piston components, using Meehanite cast iron in this instance. I also had to make a new comp screw due to the fact that someone with more enthusiasm than understanding had tapped the head 1/4-32, presumably with an ill-considered view towards converting the engine to glow-plug operation.

I was very careful to exactly replicate all of the dimensions that affected the engine's working geometry. Since all of the other components remained original and unmodified, the resulting engine is a properly-made Deezil built strictly to the original Gotham Hobby pattern in terms of its functional design. As such, its performance should be fully representative of that to be expected from one of the better-made earlier originals which I personally now believe to have existed.

What an opportunity! Here we have a replica AHC diesel which is as close to the original as it's possible to get today given the fact that there are no originals to refer to as prototypes, along with an example of the Gotham Hobby Deezil that is properly fitted but otherwise identical in all respects to the original. What fun—let's put them on test together to see how the two competing sets of Winston brothers fared in the diesel design sweepstakes!

The AHC and Deezil Models Head to Head

The rebuilt Deezil was all ready for testing, having been carefully run in for over an hour following its rebuild and then given a fair number of demonstration runs over the years for the benefit of the vast herd of unbelievers (all of whom remain that way despite my efforts!). All fits are excellent and the engine has a "silky" feel when turned over, with outstanding compression. It's an excellent starter, needing only a few finger-chokes to get sufficient fuel into the cylinder. For the present test, it ran very smoothly indeed once going and was very easy to set. The brazed-up cylinder assembly has so far shown no hint of failure. It must be said that the standard of brazing on these engines is very good.

The one problem encountered during testing was the fact that the venturi became loose in its thread and started to unscrew (see above image). After getting the engine back home, I treated the venturi installation thread with medium-strength Loctite. This should completely cure the problem and can be recommended for any original Deezil which can be persuaded to run.

I had no actual figure for the amount of running time which the AHC replica in my possession had received. Builder Ron Chernich advised that he ran all of them on the bench until they would hold a speed above 7,000 rpm on an APC 8x4 GF airscrew—typically around 20-30 minutes. I had no information regarding whether or not any subsequent owner had run the engine further. Regardless. the engine still felt a bit stiff to me, so to be on the safe side and to give the engine a fair chance I elected to give it a further 30 minutes pending the commencement of the tests.

Ron had warned me that his AHC replicas had a tendency to run hot. I thought this a little surprising given the low-tech design of the engine, but initial tests confirmed Ron's advice completely. Although the engine was very easy to start, never needing a prime at any time, it proved difficult to establish an optimum needle setting and the engine sagged quite markedly when warmed up. After stopping, it felt quite a bit hotter than I'd generally expect an engine of this specification to feel. This may have been partially due to residual stiffness, although this was insufficient in my view to be a major cause for the overheating.

Close inspection of the unit revealed a possible cause for both of these issues. Ron used an original AHC case and jet to make this engine, and it turned out that the jet was considerably too short for the socket into which it screwed. As a result, the jet orifice was set at the base of a "pocket" in the side of the venturi tube rather than being at the surface. This is very far from an ideal situation for a surface-jet needle valve assembly.

It's an often�overlooked but absolutely critical fact that air-cooled 2-stroke engines are actually fuel-cooled to a very significant extent. The incoming mixture makes a major contribution to cooling as it passes through the engine, so it's highly desirable that it be at the lowest possible temperature coming in.

Carburetion plays an important role here since efficient atomization of the fuel draws the maximum evaporative latent heat out of the fuel, cooling the resultant mixture and thus maximizing the contribution to cooling made by the incoming fuel. It can also improve combustion quite significantly. Present-day team race exponents know all about this, hence their efforts to thermally isolate the spraybar from the rest of the engine. Indeed, Pete Buskell of tuned E.D. Racer fame was well aware of this factor way back in the 1950's —remember his spraybar modifications in Model Aero Engine Encyclopaedia aimed at improving fuel atomization? �They work ...

Reasoning that improving the AHC replica's carburetion might help with the heating issue, I made a new jet having a longer thread which stopped right at the venturi wall. In place of the squared-off inner end of the standard AHC jet, the tip of the replacement jet took the form of a shallow cone which protruded slightly into the venturi throat. I have found such a design to give excellent carburetion with surface needle valves since it promotes high-speed airflow directly across the jet orifice. Believe it or not as you will, this completely cured the problem—the engine would now needle flawlessly and ran without excessive heating at all speeds. Starting qualities remained outstanding.

Now that I had both engines performing at their best, it was time for the test! Neither of these designs appeared to have much in the way of high-speed potential—I was expecting both to be of the high-torque low-revving "slogging" variety. I chose the test props accordingly, with the following results.

| Prop | Deezil | BHP | AHC | BHP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10x6 APC GF | 6,200 | 0.088 | 4,700 | 0.038 |

| 10x4 Taipan GF | 7,300 | 0.099 | 5,900 | 0.053 |

| 9x6 APC GF | 7,500 | 0.103 | 6,100 | 0.055 |

| 9x4 APC GF | 8,400 | 0.110 | 6,700 | 0.056 |

| 8x6 APC GF | 8,800 | 0.112 | 6,900 | 0.053 |

| 8x4 APC GF | 9,600 | 0.096 | 7,500 | 0.046 |

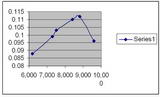

As can be seen, the AHC more or less lived down to my expectations—the engine was pretty much done by around 7,000 rpm. It seemed to peak in the vicinity of 6,500 rpm, at which speed it was making around 0.058 BHP. Most contemporary diesels of half the displacement would equal or exceed this figure, albeit at somewhat higher revs. As an example, a "Bicycle-Spoke" Frog 100 Mk II tested at the same session managed 7,000 rpm and 0.064 BHP on the same 9x4 airscrew.

My personal impression is that this engine is limited primarily by its induction system—it seems to have self-asphyxiation designed into it by virtue of that ultra-skinny venturi. Regardless of the reasons, the power curve shown here was derived using established power absorption coefficients for the props involved.

Based on the above figures, it seems clear that the right props to use for flying would be the 10x4 or 9x6. These would allow the engine to reach its peak in the air. They would also shift a fair bit of air at a high level of working efficiency. Propped in this way, the engine would doubtless have been an excellent performer in a small free-flight sports model, although its low power and fragility would have greatly limited its usefulness in control line.

By contrast, the Deezil with its relatively open cylinder porting and far larger 0.218" (5.56 mm) diameter intake venturi proved to be an excellent performer, peaking at a far higher speed than I had anticipated. It managed 7,300 rpm on the 10x4 prop, thus exceeding the performance of the refurbished NIB example described earlier by some 400 rpm. However, it is far better run-in than the NIB example. Taking this factor into account, the two engines seem to be close enough on this prop that the performance of the more "experienced" example may be taken as fully representative of that to be expected from a fully run-in engine of standard specification.

I had thought that the 9x4 prop at 8,400 rpm would be pushing the Deezil past its peak, but I was quite wrong! The above figures imply a peak output of around 0.113 BHP @ 9,000 rpm—far higher on both counts than I was expecting. The curve displays the sharp drop-off past the peak which we expect to see with side-port engines, but the Deezil proved more than willing to rev past that point if called upon to do so. However, vibration was definitely becoming an issue as speeds approached 9,000 rpm.

Notwithstanding the latter comment, this is a highly commendable performance, handily beating Lawrence Sparey's figures of 0.109 BHP @ 7,000 rpm for the contemporary 2 cc E.D. Comp Special (Aeromodeller, May 1948). The graph here shows the BHP curve for the Deezil based on our usual "calibrated" prop power absorbtion figures (see Gordon Cornell's Model Engine Development series, Part 9).

Now I recognize that the example tested is very far from being a true Gotham Hobby product—it has an accurately-fitted Meehanite piston for one thing, as well as properly finished and fitted working parts throughout. However, it must be re-emphasized that in functional design terms it remains bog stock—the crankcase, cylinder, porting, cooling jacket and induction system are pure unadulterated Gotham, brass main bearing bushing and all! Same goes for the prop mounting hardware. Since I reproduced the dimensions of the original parts exactly and didn't make any modifications to the cylinder porting, the timing remain unaltered.

The above figures are thus completely representative of the original engine's true design potential. Looked at from this perspective against contemporary diesel standards, it becomes crystal clear that there was nothing whatsoever wrong with the design of the Deezil—it was appallingly poor execution that let it down.

The AHC and Deezil Replicas

We've already seen that the AHC diesel never reached the series production stage—only a few prototypes appear to have been produced by AHC, and none of these are known to have survived. As a result, any AHC diesel which may be encountered today will be a replica.

A number of individual examples of this engine have been completed in various parts of the world by home constructors who were granted access to cases and drawings. Both Bert Streigler (USA) and the late Russell Watson-Will (Australia) produced outstanding examples. There may well have been others in addition.

The closest thing to date to a series production effort in connection with the AHC was the previously-mentioned short run of a dozen or so replicas produced by our talented Editor, Ron Chernich. This is as faithful a replica as anyone could produce today given the absence of any original prototypes. As stated earlier, Ron has documented this project very thoroughly in a separate series of articles on this site. As far as I'm aware, there have been no subsequent attempts to produce a series of AHC replicas.

However, the same cannot be said of the Deezil! Quite apart from a number of successful refurbishments of original examples like my own pair, there have been at least two initiatives centred around the commercial production of the engine in replica form.

The first of these came from Australia's most respected model engine designer and manufacturer, the late and much missed Gordon Burford. Recognizing the relative scarcity of good examples of the Deezil together with the virtual non-existence of operable examples, Gordon produced a limited run of Deezil replicas in the 1980's. In keeping with Gordon's usual practise, these were manufactured to the very highest standards. They are not exact replicas—Gordon made a few practical changes such as the lock-nut carburettor mounting, the comp screw design, a far more substantial prop driver and the provision of a hang tank. However, they are superb runners which rightly command quite high prices today on the collector market.

Gordon's son Peter has kindly shared a delightful vignette with us which arose in connection with this replica. A prospective customer who was clearly familiar with the reputation of the original Deezil asked Gordon if the engine that he was contemplating buying would run. "Of course not!" replied Gordon, "It's a replica!" Needless to say, the sale was immediately consummated.

In the late 1980's a new name entered the picture—Classic Old Time Engines (COTE) of Perrysburg, Ohio. This company was established by Don Belote, an avid engine collector and home machinist who was also very active in the Toledo Weak Signals R/C club for many years.

Don arranged to have a series of Deezil replicas manufactured by others and sent to him for distribution to his fellow collectors and vintage fliers. For some time the source of these replicas remained under wraps, but eventually the truth emerged—they were manufactured to Don's specifications by CS in China! This was confirmed by Don personally when asked about it by a friend of his. Don also arranged for the manufacture of a run of Micro Diesel replicas by CS.

Like their Burford predecessors, the COTE replicas are readily distinguishable from the Gotham originals. For one thing, their cases are blasted to a nice matte finish, the name DEEZIL being CNC-engraved into the front of the case rather than being cast in relief onto that area. In addition, they have far more substantial mounting lugs. The compression screw differs from either of the original Gotham styles described earlier, and the cooling jacket profile is also somewhat different from that of the originals. The intake venturi tube is secured with a lock-nut, while the spraybar is of more conventional style, being left unthreaded over the portion contained within the venturi. Finally, the prop mounting arrangements are very different, being based upon the use of a split collar to mount the alloy prop driver, with the flat on the forward portion of the crankshaft being omitted.

Once Gordon Burford became aware that CS had entered the Deezil sweepstakes and were in a position to flood the relatively limited market with their far cheaper replicas, he elected to abandon the production of the Burford Deezil and move on to other designs. This left the field open for CS and Classic Old Time Engines. The marketing of the engines under the COTE banner ended at some point in the 1990's, but CS carried on for some time thereafter, selling the engines under their own name in standard CS boxes. Examples of replica Deezils may accordingly be encountered under both names, and it's important to understand that they are in reality one and the same product. The early ones packaged by COTE are generally of higher quality—they were individually checked by Don Belote and given a 10-minute test run on a 10x5 Zinger prop. In addition, they were individually serial numbered both on their backplates and on the box. Otherwise, the engines marketed under the two names were essentially identical.

Don Belote reportedly passed away a few years ago, but the legacy of the CS replicas that he brought into existence remains. The quality of those marketed directly by CS is rather variable, but a good one makes a very acceptable engine for running and sport-flying purposes. Prop-rpm figures published on the various modelling forums imply a level of performance very much in line with that reported earlier for my own refurbished "original" Gotham Deezil.

In 1994 Roger Schroeder's "Winged Engines" column in Strictly Internal Combustion (SIC) magazine introduced readers to a Deezil replica, built from Roger's sand castings. This series spanned issues 39 through 43, which are still (2011) available from the publisher and editor, Mr. Robert Washburn, 24920 43rd Ave S, Kent WA 98031, USA. Roger also produced a run of casting kits for the engine to complement the articles. A number of engines have been successfully completed by various constructors using these castings, opening up the possibility that the odd example may be offered for sale on eBay or elsewhere.

Roger was kind enough to donate the plans for his reproduction (re-drawn in Motor Boys International style by Ron Chernich) to the Motor Boys Plan Book, initially published and sold through the AMA. This is long out of print, but an updated and expanded version on CD can be bought through this web site. Some highlight's of construction are also available on the Deezil Construction Log page.

As a general rule, Roger did not develop full size reproductions, his intent being to circumvent any potential use of his castings by unscrupulous individuals presenting the resulting engines as originals. However, in the case of the Deezil his sand-cast crankcase castings (produced using an original die-cast case as a pattern) were full size. Roger figured that anyone should easily be able to tell a repro Deezil from an original—the repro would run!

The Aftermath